Assassination nation

Violence is a long-held American idea—as is the hope that violence will, one day, be eradicated.

On March 1, 1954, five Members of Congress were shot on the floor of the U.S. House of Representatives. The would-be assassins were four members of a Puerto Rican Nationalist Party. The quartet had booked one-way bus tickets from New York City to Washington, D.C.; snuck weapons into the viewing gallery above the House of Representatives; and opened fire shouting “Viva Puerto Rico libre!”—“Long live free Puerto Rico!” while unfurling a Puerto Rican flag. The motivation for the attack was, ostensibly, Puerto Rican independence; Puerto Rico was annexed by the U.S. after victory in the 1898 war with Spain and has remained an American territory ever since.

The four shooters were arrested, charged, found guilty and spent varying lengths of time in prison before their sentences were commuted. Because none of the Congressmen died, the shooters were convicted of assault as opposed to murder. Representative Alvin Bentley (R-Mich.) was the most seriously wounded, a bullet piercing his chest and striking his lung, diaphragm, liver and stomach before exiting his back. Doctors that night told reporters he had a 50/50 chance to live, yet after a 1.5-hour operation by the next morning he was stable. Confined to a wheelchair later in life, he died in 1969 at the age of 50.

I don’t recall exactly when in I first learned about this incident, which never appeared in any of my high school history textbooks. But I do vividly recall reading an article in an academic journal a few years ago that celebrated it. Without naming the author or the journal, I will simply say that the scholar—a female academic at a U.S. university—quite openly suggested that the attempted murders had been justified as part of Puerto Rico’s decolonization struggle. She then linked the attempted assassinations in 1954 to the cause of contemporary Palestine. There’s no evidence that I’m aware of that the four Puerto Rican nationalists of 1950s New York had connections to the Middle East. The through-line, for this contemporary scholar, seemed to be that acts of murder against perceived oppressors required neither apology nor justification.

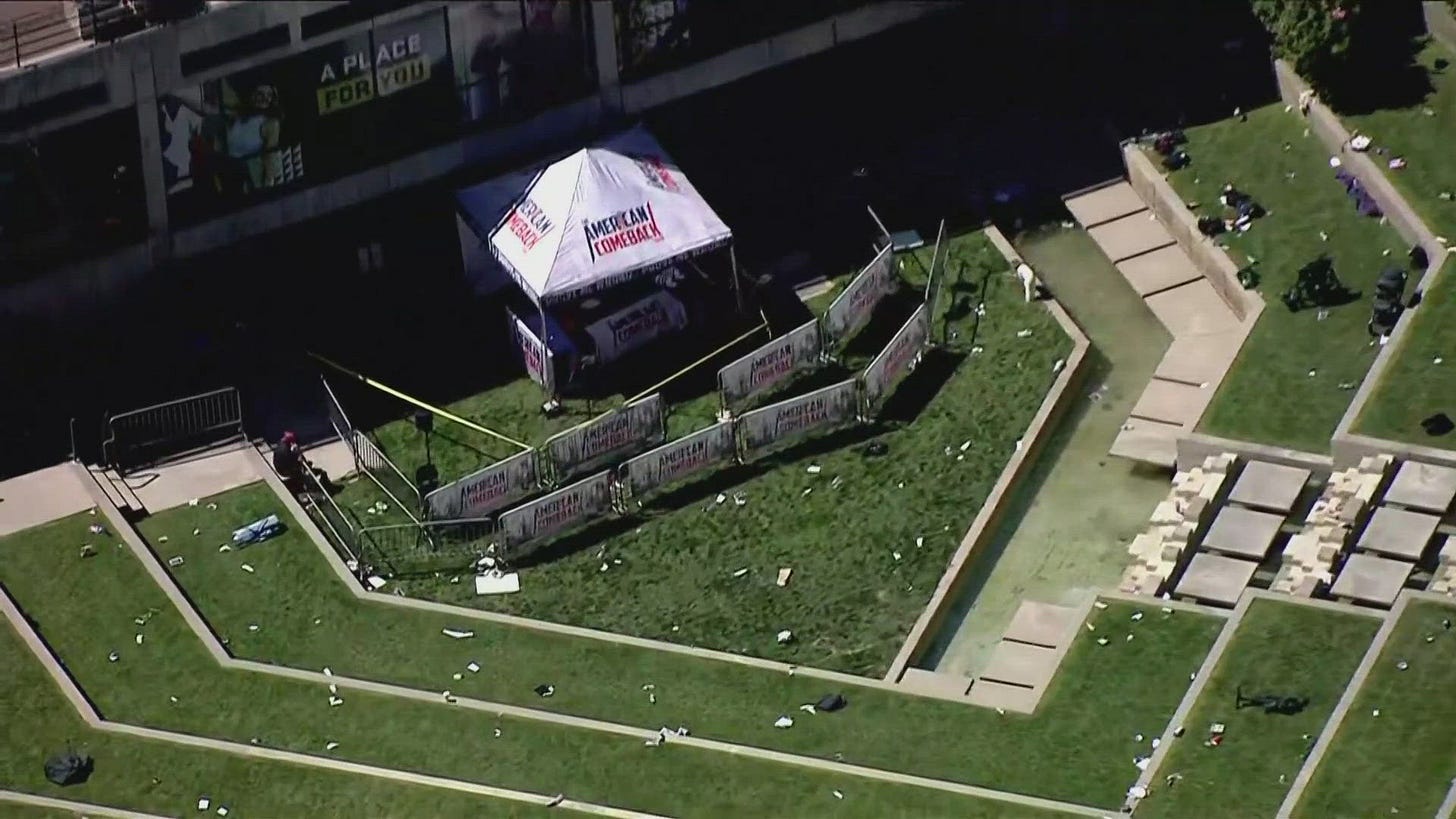

If such sentiments sound familiar, it’s because they are omnipresent in contemporary America. Just within the past year or so, the CEO of United Healthcare was assassinated in the streets of New York City; a state representative and her husband were assassinated in Minnesota; the current President was nearly assassinated in Pennsylvania; two employees of the Israeli embassy to the U.S. were assassinated in Washington, D.C.; the home of the governor of Pennsylvania was set on fire by an arsonist; and Conservative activist Charlie Kirk was assassinated in Utah.

(This excludes 47 school shootings so far this year, 600 threats against government officials last year, and a Molotov cocktail thrown at a crowd of demonstrators in June that killed an 82-year-old woman in Colorado.)

More startling than the violence has been their justifications—and, in some cases, wanton approval. Healthcare executives, political leaders, and those affiliated with the State of Israel are perceived, by some Americans, to be oppressive forces. Ergo, anyone involved in supporting such forces is a fair target for violence. In my own personal interactions, I have been taken aback at how gleeful and approving many people have been of Charlie Kirk’s murder in the weeks since it occurred. Publicly, they may express remorse. Privately, they believe something very different.

What has led to such vitriol? Like all things, a historical perspective offers some inroads for making sense of these phenomena. While 19th century America was an atrociously violent place—lynchings, street riots, slavery, rebellions, massacres of indigenous populations and a war between the Union and the Confederacy—political assassinations were not celebrated. President Lincoln’s assassination in 1865 cast a pall over the entire country that lasted for weeks. Newspapers from 1881 report that the assassination of President Garfield drew anger and sorrow nationwide. The assassination of President McKinley in 1901 (technically one year after the 19th century had ended) was not cheered beyond anarchist circles, and was met with fierce backlash against anarchists in the U.S. for their alleged complicity.

Such sentiments began to change in the 20th century, particularly after World War II. Among the shifts wrought by the Second World War were rhetorical and discursive evolutions in how violence against political actors was spoken of. The bloody war that liberated Europe from totalitarianism had resonated across the globe, particularly among nations that were oppressed by European imperialism in Africa, Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean. If fascism in Europe needed to be defeated with violence and bloodshed, would that not also apply to the imperialism that Europeans had inflicted upon colonized lands?

In the decolonization rhetoric of the post-war era, one finds a shift in the tactics and justifications for violence as a means towards achieving political objectives. One of the most influential voices for these ideas was Frantz Fanon, though he was not the only one. Fanon (who died in 1961) framed violence as an inevitable tool of resistance. The colonizers had used violence to subjugate native peoples; native peoples, thus, had a right to channel their anger and mistreatment into a violent response. Acts of violence were the only means by which the colonizer would take the colonized seriously and see them as an equal, thereby making negotiations for liberation possible. Violence would serve as the cleansing activity that would rid the world of exploitation and re-establish self-respect and self-worth for those who had been denied it. The endpoint would be the forging of a socialist society free from capitalism and imperialism.

In the case of Puerto Rico, these ideas were already beginning to express themselves in 1946, shortly after World War II, and before Fanon published his seminal works. The Puerto Rican “Independentistas” had grown weary of the U.S. Congress not acting meaningfully enough to further Puerto Rican independence. Hence why the U.S. House of Representatives was selected as a target in 1954. An act of violence in the U.S. Capitol would draw attention to the struggle and force policymakers in Washington to take the Puerto Rican independence movement seriously. Speaking to newspaper reporters following the attack, Lolita Lebrón, the female ringleader of the assassins, expressed no remorse for what she had done. “I do what I must for my country,” she reportedly said from her jail cell. She insisted, according to the Key West Citizen, that members of her group were “patriots—not criminals.” She vowed to continue the struggle, and indeed, once President Jimmy Carter released her from prison, Lebrón returned to Puerto Rico to work as a speaker, writer and demonstrator. After she died in 2010 at the age of 90, the Workers World Party—the self-described “revolutionary Marxist-Leninist party”—eulogized her as a hero, citing her as an example of “La Patria es valor y sacrificio”, which translates to “Homeland is courage and sacrifice.”

The Workers World Party is a useful website to peruse when trying to reconcile some of the justifications for political violence that pervade contemporary America. On their about page, the party states plainly that they do not “leap on the bandwagon” of criticizing or chastising those who use violence to overthrow perceived oppressive structures. This includes, for example, Hamas, which the Workers World Party openly supports, praising their recent terrorist attack in Jerusalem that killed six Israeli civilians, parroting their propaganda and calling on fighters everywhere to “set our land on fire under the feet of the usurping zionists.” Their party platform includes praise for the former Soviet Union, a call to dismantle NATO, and a global revolution that would eradicate capitalism and replace it with socialism. Their positions are not so dissimilar from that of the Democratic Socialists of America, who also call for the abolition of NATO, cessation of relations with Israel, normalization of relations with Iran, North Korea and China, and the abolition of capitalism in favor of socialism. (One of their party members, Zohran Mamdani, is the favorite to be the next Mayor of New York City).

While some pundits may claim such ideologies are solely the purview of the political left, similar sentiments have been emerging on the political right throughout the 20th century and into the 21st century. One of the most influential figures in this regard was Murray Rothbard, an economist whose writings have grown in stature and legend since his passing in 1995. During his lifetime, Rothbard did not mince words on how he viewed the post-war political struggle: a politics of war. Rothbard and his disciples—of which there are many—argued against any measured and judicious discussion of societal issues with the political opposition. Instead, he argued for a relentless and confrontational politics of resentment. “We need,” Rothbard once wrote, “an adherence to the military metaphor, to the concept of us vs. them, good guys vs. bad guys... for eventually we must drive the wooden stake through the heart of the Enemy.”

The notion of a political enemy whose death must be the final outcome of the struggle was not confined to non-fiction. Arguably one of the most influential books on the far right in the 20th century was The Turner Diaries, written by a former professor who was an adherent of the American Nazi Party. The Diaries are a fictional account of a future race war between whites and their alleged enemies, i.e., Jews, Blacks and the American government. The hateful plot entails a series of lynchings, suicide attacks and bombings executed as part of a “patriotic fight” to take back the country. One of the attacks imagined in the book is the bombing of an FBI headquarters, which reportedly inspired Timothy McVeigh’s bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City in 1995, murdering 169 people. The book has inspired other murders by white supremacists in the U.S., and been cited—among many titles—by numerous hate groups, of which the Southern Poverty Law Center now tallies more than 1,000 in contemporary America.

It's important to recognize, then, that the violent ideas coursing through our political discourse are not new. They have long histories, histories that intersected and co-existed with the “post-war liberal consensus” of the previous century that media pundits and Presidential historians are fond of recalling. Such is one of the perils of looking at the past through rose-colored nostalgic glasses; it tricks us into believing that some ideologies have only emerged with the advent of social media or in the wake of 2016. In truth, their origins long pre-date our current times, and, indeed, long pre-date America’s young people who seem so enamored with them.

So, why have such ideas gained such traction now? That, too, has a complex history; far too complex for this short article. Needless to say, when the cost of living for most Americans is impossible, healthcare for most Americans unaffordable, our politics intractable, and our wars seemingly unendable, it stands to reason that people would feel disaffected and disenfranchised by existing systems and seek out radical communities beyond them. Couple those frustrations with the realities of persistent discrimination, wealth inequality, non-responsive institutions and environmental degradation, and it can feel as though any hope of changing the existing system through the existing system would be futile. Revolutionary action becomes more attractive as the only option for systemic change. If violence is a necessary part of that revolutionary action, according to certain political voices that have gained more exposure through social media and the Web, then such violence will increasingly be rationalized. Reactionary violence then becomes rationalized in response.

In July 1881, after President Garfield was assassinated, the weekly Louisianian, a Black newspaper in New Orleans, published the following words: “The assault upon President Garfield is an astounding assault upon the nation. The shot fired by a madman is a shot fired at all of us.”

Today it feels like the inverse is true: the shot fired by a madman is a shot fired on behalf of all of us. The killer of a healthcare CEO acted on behalf of those aggrieved and wronged by the American healthcare system, we are told. The murder of Israelis in Washington, D.C., was done on behalf of those angered by what is happening half-a-world away, it is said. The murder of a Conservative political activist was done on behalf of those who were insulted or aggrieved by his words, social media tell us. In an era where the divide between fantasy role play and reality has become indistinguishably thin, political assassinations mediated through screens serve as yet another activation of our brains’ mirror neurons. When we watch sports, our mirror neurons make us feel as though we are playing along, experiencing similar emotions as the players. When we watch someone play video games, our mirror neurons make us feel as though we are experiencing what the players are experiencing. And when individuals take the call for violent revolution into their own hands—almost surely meaning that they, too, will be killed or incarcerated—our mirror neurons make the oppressed, marginalized, disenfranchised or victimized among us feel as though we, too, have actively participated in the struggle. When those expressions become highly visible online and rewarded by the social media ecosystem, they are replicated by others seeking similar adulation.

This is not a phenomenon relegated to one side of the political spectrum. In today’s America, toxic combinations of ideas on the Left and Right—oxidized by the incentive structures of social media, worsened by the immovable realities of American political life, stoked by propaganda and disinformation, and fueled by widespread access to firearms—have turned political assassinations from solemn moments of reflection and introspection into something akin to a spectator sport, where we “cheer” or “boo” from the sidelines while consuming endless media about the topic from multiple angles. The cycle stokes our emotions and fuels our infatuation with the effects of violence, which only exacerbates the likelihood of it happening again. Invariably the assassination attempt becomes adaptable as a piece of evidence into a larger narrative: evidence of the necessity to destroy the Left, evidence of the necessity to destroy capitalism, evidence of the imperative to restore American civility, etc. All the while, would-be assassins, themselves often alienated individuals, become further enamored by the attention they may earn from committing such acts and desensitized to the consequences of destroying a fellow human being’s life and family.

Is there a solution? Perhaps if our politics were better able to solve people’s problems, resolve structural inequalities, invest in countering disinformation and reverse environmental degradation that would lead some people away from the fringes and make them more optimistic that deliberation and debate can produce meaningful policy outcomes. Political assassinations are not solely an American phenomenon: Haiti, Japan, Ukraine and others have each experienced their own, as have many other countries. But part of being an American is believing that change through democracy is possible, and that hope and optimism for a better tomorrow are not empty promises.

Part of the solution, then, it seems to me, must be to not lose hope that an end to violence is achievable—even when all evidence points to the contrary.

Have a peaceful week,

-JS

Your work is a gift. On point, beautifully written, and as always, with an accurate historical perspective. Thank you!

Great essay.