Behind the scenes at the Library of Congress

A sneak peek inside the world's largest library

Longtime readers of this newsletter know that for seven years I worked at the U.S. Library of Congress. The first 2.5 years were spent collecting the stories of America’s war veterans for the Library’s Veterans History Project; the next 4.5 years were spent bringing scholars from around the world to the Library to conduct research in the Library’s John W. Kluge Center, and sharing that research with Members of Congress, federal policymakers and the public.

I often tell people that my seven years at the Library were the most intellectually stimulating of my life. To be around such brilliant scholars and staff every day, amid the world’s largest collection of accumulated wisdom, is nearly impossible to describe. It changes you as a person, and it changed me for the better.

So, it should not be a surprise that I go back to the Library every chance I can (including writing and researching large portions of History, Disrupted there). Since I have been teaching a course on bringing history into policy this summer at the Maxwell School for Citizenship & Public Affairs, I decided to bring my students to the Library of Congress to learn about the various ways that history at the Library informs the legislative process. I reached out to a few former colleagues for help in planning a behind-the-scenes tour for my students, and, as usual, the Library did not disappoint.

I thought I’d use this week’s newsletter to share with you some of what we saw.

Readers may not be aware that the Library of Congress is divided into numerous service units, divisions and reading rooms. Some of that is for administrative and bureaucratic reasons: budget planning, staff allocation, etc. When it comes to the Library’s collections—now totaling more than 175 million items in 470 languages—much of the material is organized by format.

The Library has:

A manuscripts division

A prints & photographs division

A motion pictures, broadcasting & recorded sound division

A music division

A newspaper & periodicals division

etc.

Each of these divisions has reading rooms where patrons can—using their library cards—view materials and conduct research. Library of Congress reader cards are free and available to anyone over the age of 16. If you’ve never gotten an LC reader card and looked at material in one of the Library’s reading rooms, I would highly recommend it. It’s the closest you’ll come in your lifetime to feeling like Nicholas Cage.

For this tour, I reached out to Meg McAleer, a former colleague and current senior archivist in the Manuscripts Division. Meg is a Ph.D. historian with a specialty in modern American history; back in 2015, she was interviewed by NPR for her role in organizing the Rosa Parks papers, which are now at the Library of Congress. I asked if she could pull out some “treasures” for my students to look at that would touch on the intersection of history and policymaking. Here is some of what she showed us, along with her annotations and research:

Alexander Hamilton’s notes on the Articles of Confederation (1787)

Readers may remember the Articles of Confederation from high school history class. Created in 1777, the articles were the initial agreement between the new American states that, while aligning the states under a common government, gave that government very limited powers. By the mid-1780’s, the Articles were proving disastrous: the government could not tax, could not regulate commerce, had a depleted treasury and was dealing with massive inflation. Disputes over taxation, trade, war pensions and land were tearing the country apart. In summer 1787, a group of delegates re-assembled to create an entirely new Constitution. Meg showed us Alexander Hamilton’s hand-written notes on the deficiencies of the Articles of Confederation, including a lack of common defense and the power to contract debt without the power to pay it. Hamilton would later articulate many of these issues in The Federalist Papers.

(As an aside, I wrote a long piece in this newsletter about my thoughts on the musical Hamilton. Upgrade to a paid subscription to read it).

Abigail Adams letter to her sister (1799)

Abigail Adams was the wife of John Adams, a Boston lawyer who would eventually become the second President of the United States. She was a prolific writer and an advocate for women’s rights. Her most famous letter is one written in 1776 that urged the Continental Congress to “remember the ladies,” advocating for women’s rights under the law and for women’s education. As first lady, she wrote this letter to her sister Elizabeth Smith Shaw Peabody in 1799, in which she said that she would, “never consent to have our sex considered in an inferiour point of light… if a woman does not hold the Reigns of Government, I see no reason for her not judging how they are conducted.” Adams’s letter is a reminder that lest anyone tell you that fighting for women’s rights is a recent phenomenon, women have been advocating for participation in government and for equal treatment under the law since the very establishment of our republic (and, truly, since time immemorial).

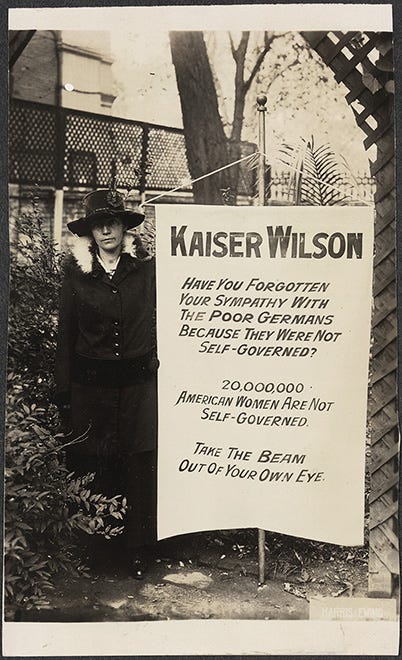

Virginia Arnold holding “Kaiser Wilson” banner (1917)

This photograph by Harris & Ewing depicts a woman named Miss Virginia Arnold. Arnold was originally from North Carolina, became a student at George Washington University and Columbia University, and then a school teacher. By 1916, she had risen to become the executive secretary of the National Woman’s Party (NWP). In January 1917, the N.W.P. began picketing The White House demanding ratification of a constitutional amendment that would grant women the right to vote. Initially, President Woodrow Wilson tolerated the demonstrations, but once the U.S. entered World War I, criticism of the government became treasonous. Arnold was put in jail for three days in June 1917, and by August 1917, sailors and soldiers were attacking suffragists for comparing President Wilson to German emperor Wilhelm II. Yet the N.W.P. persisted, highlighting the government’s hypocrisy of supporting democracy abroad while denying its women citizens at home the right to vote. By fall 1918, their persistence paid off when Wilson finally endorsed the 19th Amendment.

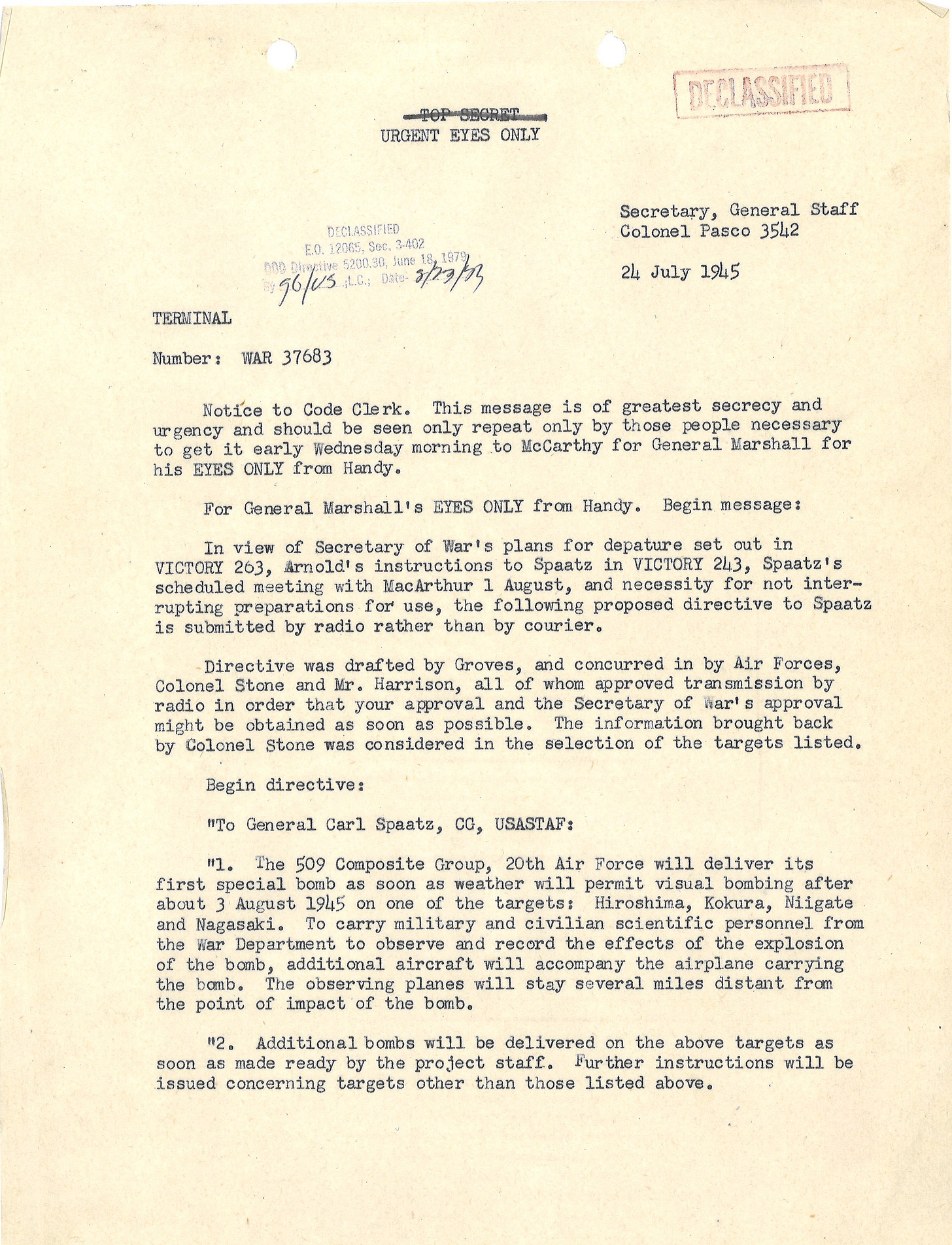

Directive to drop an Atomic Bomb on Japan (1945)

In July 1945, Carl Spaatz was chief of the U.S. Strategic Air Forces in Japan and Harry S. Truman had only been President for slightly more than two months. Truman knew virtually nothing about the “special bomb” being developed by the Manhattan Project, learning about the first detonation of an atomic bomb in New Mexico while he was at the Potsdam Conference in Germany planning the post-war reconstruction of Europe. Truman informed Stalin about the weapon (Stalin already knew), and on the same day received a top secret cable from Manhattan Project director Leslie Groves authorizing the deployment of the “first special bomb as soon as weather permits visual bombing after about 3 August 1945 on one of the targets of Hiroshima, Kokura, Niigata and Nagasaki.” Truman agreed, and the order was relayed to Spaatz. On August 6, 1945, the first of two atomic bombs was detonated over Japan; Truman made sure that he was away from Potsdam and on his way home when the bomb fell.

(Note: I haven’t yet seen the movie Oppenheimer; I will probably wait until it arrives on streaming. If you’ve seen the film, let me know your thoughts on it in the comments.)

Notes during the Cuban Missile Crisis (1962)

To quote McAleer’s research directly: “Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for Intelligence and Research Thomas Lowe Hughes was an acute observer at high-level meetings during the Cuban Missile Crisis. Shown here is a selection of his notes beginning October 15, the day the first U-2 photographs were processed, and ending October 22, the day President Kennedy addressed the American people on television. The notes record the rapidly evolving intelligence from U2 planes, the lack of consensus between the "War Hawks" and "Doves," the myriad of conflicting options presented to the president, a hint at process (“decision making through speech writing”) and, above all, the interpersonal dynamics. As new intelligence continued to become available, Hughes quotes President Kennedy's observation that "This is [the] most dangerous situation since the end of [World War II].”"

This is, obviously, just a tiny sample of what the Library contains. It holds more than 25 million books, 77 million manuscripts, nearly 6 million maps, 8 million items of sheet music, and 15 million photographs. It has the papers of U.S. Presidents from George Washington to Calvin Coolidge, drafts of the Declaration of Independence and Bill of Rights, Walt Whitman’s papers, Ralph Ellison’s papers, the NAACP papers, Rosa Parks’s papers, scores of indigenous and native artifacts, the first map ever to have the name “America” and the contents of Abraham Lincoln’s pockets the night he was assassinated, among many treasures. In addition to the items above, my students also got to see Jackie Robinson’s contract to play baseball; a postcard from Martin Luther King, Jr. to Rosa Parks; a memo from Abraham Lincoln to himself and his cabinet members; and testimony from the Salem Witch Trials.

After viewing these treasures, we met with the Congressional Research Service (CRS), which is a crucial part of the Library that I’ve not yet even mentioned. Founded in 1914, CRS is the research arm of the U.S. Congress; each year, CRS produces thousands of research papers and answers thousands of research queries from Congress and its staff on subjects as diverse such as economic policy, foreign affairs, domestic terrorism and the federal government itself. CRS also helps maintain Congress.gov, which tracks all current and prior legislative activities: bills introduced, bills referred to committee, bills signed into law, which Members of Congress supported which bills, caucuses, nominations, hearings and roll call votes. It’s an amazing resource, and it’s free to use.

Finally, no visit to the Library would be complete without a tour of the Thomas Jefferson Building. Begun in 1873 and completed in 1897, the beauty of this Italian Renaissance style building never gets old (in my humble opinion). Of the seven years I worked at the Library, 4.5 were spent working in the Jefferson building, and I never took it for granted that I got to walk into such an extraordinary structure each day.

As it was described many years later, the Jefferson building’s “monumental conception and design, combining architecture, sculpture, and painting on a scale unsurpassed in any American public building, represented a unique architectural achievement. The Library’s glittering dome, plated with 23-carat gold, capped an elaborately decorated facade and interior which were enriched by works of about 50 American artists. A contemporary guidebook exclaimed that ‘America is justly proud of this gorgeous and palatial monument to its national sympathy and appreciation of Literature, Science and Art.’”

My former colleague at the Kluge Center was gracious enough to take me and my students to the top of the Jefferson Building to look up at the gilded ceilings and to look down upon the Main Reading Room.

All-in-all it was a terrific day spent at the Library, and one that opened the eyes of my students to the activities of this institution, and its possibilities for informing their work as they move forward in their careers.

Most importantly, you do not need to have formerly worked at the Library, or have special access, to enter these buildings. Anyone can visit and use the Library of Congress. Whatever subject you’re interested in—in whatever languages—the Library of Congress has something for you.

What you encounter there just might change the way you look at history or policymaking—and, likely, both.

Have a learned week,

-JS

Very cool.