Diversity at the Euros

UEFA Euro 2020 showed a glimpse of Europe's bright future--and its ugly past

History Club remains on break while I work on my book manuscript. Stay tuned for an updated schedule.

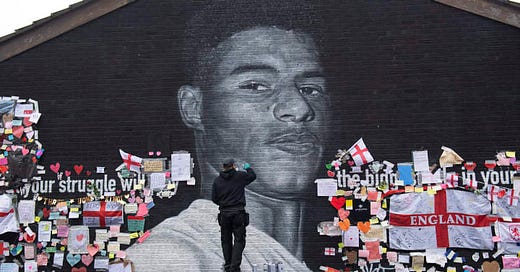

The 2020 UEFA European Football Championship concluded this past weekend with Italy defeating England in a thrilling penal…