William McKinley is not a President that most Americans—or, indeed, most people around the world—think about on a regular basis.

President Trump and his advisors, however, seem to have given considerable thought to McKinley’s presidency. Amid Trump’s threats to annex Greenland, seize the Panama Canal, impound Gaza, impose tariffs, eliminate federal agencies and repel “wokeism,” the McKinley influences are ubiquitous: from tariffs and protectionism, to American imperialism and the “White Man’s Burden.” It was not a coincidence that Trump reverted Mt. Denali in Alaska back to Mt. McKinley in one of his earliest Executive Orders.

Allow me to use this week’s newsletter, then, to refresh your historical memory on President McKinley, explain his apparent influence on the Trump Administration, and decipher, for you, what it means for America’s role in the world under Trump 2.0.

📣 Before I do, however, the second Trump Administration has marked a seismic shift in world affairs that demands historical knowledge and media literacy to understand. It will take immense energy and effort to keep up with the flurry of activity, and I need your support. If you’ve messaged me this week asking for my thoughts on what’s happening, please become a paid subscriber so I can devote more time to giving you the answers. Upgrade to paid »

🎥 I’ve also been making short videos on Instagram contextualizing news as it breaks. You can find those on my Instagram profile »

The McKinley Years

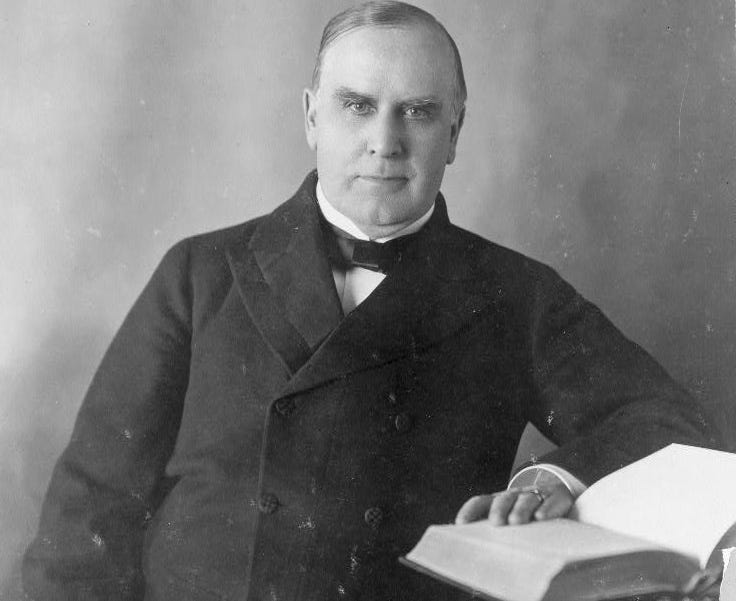

First, the basics: McKinley was a native of Ohio who fought in the U.S. Civil War, practiced law, and was staunch Methodist Christian. He entered politics in 1876, winning a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives and serving in Congress for 14 years, becoming a powerful figure within the Republican Party to include chair of the House Ways and Means Committee. After losing his seat in 1890, he successfully ran for governor of Ohio in 1892.

In 1893, the U.S. fell into a deep economic recession. Banks failed, industrial production fell, and unemployment rose as high as 17 percent. (Recessions were a regular occurrence in 19th century America for reasons too complex to explain here). The hard economic times turned the U.S. population against Democratic president Grover Cleveland, creating an opening for the Republicans in the 1894 midterm elections and the 1896 Presidential election. McKinley saw an opportunity.

McKinley won The White House convincingly, and upon taking office in 1897 instituted a series of policies that would have significant ramifications for the U.S. in the century to come:

He instituted tariffs;

Issued an executive order that dismissed civil servants;

Annexed Hawaii;

Acquired Puerto Rico and Guam;

Went to war with Spain over Cuba;

Expanded American power in the Pacific, principally the Philippines;

Bolstered the American military, particularly the Navy;

Advocated for business and industry; and

Professed a sympathy for American workers.

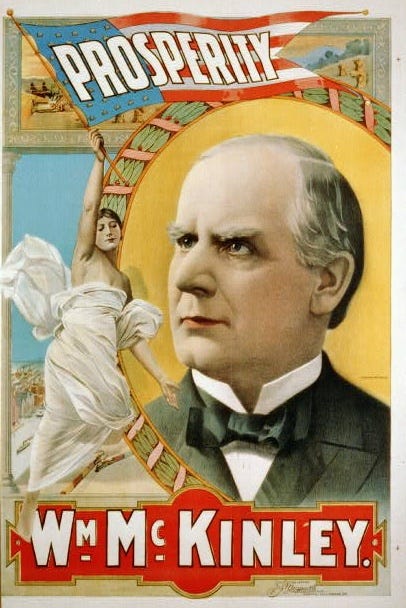

McKinley also skillfully manipulated public relations and the press, including printing nearly 200 million leaflets and posters to denounce his Presidential opponent, William Jennings Bryant, and recording the first-ever campaign film in U.S. politics. (I made a YouTube video about this with the Smithsonian years ago.)

McKinley won reelection in 1900, but his life was cut short in 1901 when he was assassinated in Buffalo, New York by a self-proclaimed anarchist named Leon Czolgosz. The assassination paved the way for Vice President Theodore Roosevelt to become Commander-in-Chief, ending the Gilded Age and ushering in a Progressive Era that would last until the end of the First World War.

Already, you may see similarities between McKinley and Trump. Both were Republicans; both were pro-industry; both were interested in expanding America’s global empire; and both were victims of assassination attempts (though, obviously, Trump survived his).

One could argue, too, that both were “America First” – perhaps, even, that McKinley was the progenitor of “America First.”

McKinley lived during a period (and, indeed, was an influential figure) when the U.S. became a global superpower. Between 1865 and 1900, U.S. exports quintupled from $261 million to $1.53 billion.[1] The fastest growth was in manufacturing where U.S. companies emerged as world leaders, exporting goods around the globe and fueling budget surpluses of hundreds-of-millions of dollars. U.S. industry ballooned during the Gilded Age with “Robber Barons” such as Rockefeller, Carnegie, Vanderbilt and Westinghouse amassing vast fortunes.

With economic power came an elevated position on the global stage. To quote McKinley biographer Kevin Phillips:

“The extraordinary progress in science, invention and industry in the United States from the Civil War to 1900 was on a scale with what Britain had achieved from 1760 to 1830 during the gathering of the Industrial Revolution. The great technological exhibitions of early Victorian Britain had stunned the world, and so did the displays in the technology-filled American Pavilion of the Paris Exposition in 1900 and the U.S. Pan-American Exposition in 1901.”[2]

America was experiencing “prosperity at home and prestige abroad,” as McKinley put it. With them came a growing exertion of American imperialism, particularly in the Western Hemisphere. When Cubans revolted against the Spanish in the 1890s, the U.S. intervened, entered into a war with Spain, and quickly routed them from the Caribbean. The U.S. used its victory in the Spanish-American War of 1898 to flex its global muscle, capturing Puerto Rico and Guam, as well as exerting colonial authority over the Philippines. (Filipinos would launch an insurgency against U.S. presence that would last for several years and kill thousands of people).

The U.S. also annexed Hawaii, deposing Queen Liliuokalani and declaring the island chain an American territory, which it would remain until statehood in 1959. By the turn of the 20th century, the U.S. had become an empire.

What drove American imperialism during the 1890s? The reasons, like most things in history, are complex.

Colonialism and imperialism were prevalent ideologies, with European nations staking claims to territories in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. As America rose in economic power, an appetite emerged among political leaders and the broader public to assert geopolitical dominance in a manner that would rival—and eventually overtake—Europe. That included the acquisition of territory, particularly in the Western Hemisphere and stretching into the Pacific Ocean.

This territorial acquisition was inextricably tied to economics. The boom in American global trade posed an existential question for policymakers, namely how to continue to find new markets to grow American influence? Territorial expansion provided the answer, particularly in the Pacific, wherein China, the Philippines and other nations were seen as emerging markets for American products. Hawaii was to be the strategic economic and military gateway that would protect American interests.

Central to this worldview was also a prevailing racial hierarchy that placed White Euro-American civilization at the top, with people of color from Hawaii, Puerto Rico, Guam and the Philippines at the bottom. Justifications for imperialism included a “White Man’s Burden” to civilize these inferior peoples, imposing Christianity and Euro-American systems onto their societies in an effort to “uplift” them.

McKinley believed in all of these ideas, and they shaped his policies as he rose through the ranks of American political leadership. It was very much an “America First” perspective, without the catchy moniker. He saw the world principally through the eyes of American dominance, manipulating the map in order to expand American influence, imbued with a “White Man’s Burden” to “civilize” and Christianize inferior peoples.

Tariffs

This worldview led McKinley, first, to tariffs.

A tariff is, essentially, a tax on foreign goods that makes them more expensive relative to similar items made domestically. In theory, this helps boost and protect local industry. The tariff—paid for by the foreign entity—also generates revenue for the government.

McKinley laid out his argument for such “protective” tariffs in an article titled “The Value of Protection” published in The North American Review. McKinley reasoned that if governments required funding in order to function, that funding must be procured either by taxing American citizens or taxing foreign imports. “The way to raise this money with the least burden upon the people is the problem of the statesman and the legislator,” he wrote.

“It would not do in time of peace to issue the notes of the government, and thus create a charge upon the people, making no provision for their payment. It would not do to restore the internal revenue system as it prevailed through the [Civil] war… It must be manifest, therefore, that the largest share of the needed income must be raised by tariff taxation or import duties.”

Taxing foreigners was superior to taxing Americans, McKinley rationalized. A tax on foreign products would also protect American businesses:

“Is it not better, therefore, I submit that the income of the government shall be secured by putting a tax or a duty upon foreign products, and at the same time carefully providing that such duties shall be on products of foreign growth and manufacture which compete with like products of home growth and manufactures, so that, while we are raising all the revenues needed by the government, we shall do it with a discriminating regard for our own people, their products and their employments?”

McKinley pursued tariffs throughout the 1890s, both as a Congressman (the McKinley Tariff of 1890) and as President (the Dingley Act of 1897) in the name of “protection,” seeking to raise money for the treasury while also ensuring the dominance of American industry. The policy failed in the early 1890s (tariffs contributed to the 1893 recession) but proved more effective in the late 1890s.

By the turn of the 20th century, McKinley believed that his actions had protected American businesses, lowered interest rates, raised wages, turned a deficit into a surplus, expanded the markets for American products and transformed the nation from “enforced idleness to profitable employment.” Interestingly, McKinley’s language on prosperity and idleness has been echoed by the Trump Administration’s communications, including the buyout email sent to government workers. “The way to greater American prosperity,” the email read, “is encouraging people to move from lower productivity jobs in the public sector to higher productivity jobs in the private sector.”

Pro-Business

Central to McKinley’s nascent “America First” worldview was the dominance of American businesses. Similar to Trump’s relationship with Elon Musk, McKinley had a wealthy entrepreneur and private citizen who helped him rise to power, a man named Marcus (“Mark”) Hanna.

A Cleveland millionaire with interests in coal, iron and steel—in addition to owning the Cleveland Herald and the Cleveland Opera House—Hanna helped McKinley get elected in 1896. He donated significant money to McKinley’s campaign; raised money from other wealthy donors; staged campaign events; and brokered support from Republican delegates for McKinley’s nomination. In archival footage of McKinley’s inaugural parade, Hanna can be seen riding in the carriage with the President-Elect.

For his support, Hanna earned a Senate seat, as opposed to a quasi-Constitutional cost-cutting cabal (more on the legality / illegality of DOGE in a future newsletter). Most significantly, Hanna evinced the importance of the private sector to McKinley’s policies. McKinley argued that a thriving business community was good for American workers. He even argued that the competition for global trade necessitated that American businesses form mega-corporations—even monopolies—in order to sustain American dominance.

If American corporations made record profits, paid lower taxes, and exported American goods to markets around the world, that was good for America overall. It would lead to prosperity, innovation and geopolitical power, and in the late 1890s, that strategy was central to his view of American empire.

American Empire

Historians have debated whether McKinley was a reluctant imperialist or an eager one, but the fact remains that under his presidency, the U.S. annexed and acquired overseas territories in ways it never had before. It also exercised its military might in ways that asserted American dominance on the global stage.

The first instance was Cuba, which had been colonized by Spain. The Cuban revolt against the Spanish garnered much sympathy in the U.S., including among American newspaper publishers. The explosion of the USS Maine in Havana harbor provoked America to wage war against the Spanish and expel them from the hemisphere. Instead of granting Cuba full independence, though, McKinley imposed conditions that resulted in a continued American presence on the island. (This is why the U.S. has a facility in Guantanamo Bay, another McKinley legacy that Trump has lauded.)

McKinley used the victory in the Spanish-American War to subsume Puerto Rico, Guam and the Philippines. He also annexed Hawaii. The pretense for these actions were economic and geopolitical; to expand American commercial dominance and signal to Europe that America was a global power to be reckoned with.

But woven within his American expansionism were threads of White supremacy. While the residents of Puerto Rico, Guam, Hawaii and the Philippines technically became part of the U.S., they were denied many privileges and rights afforded to them by the Constitution. They were viewed as “alien races,” to use the words of the Supreme Court, with the “administration of government and justice, according to Anglo-Saxon principles,” deemed to be, for a period, “impossible.” McKinley himself, in a speech to Methodist Church officials, stated that the residents of America’s territories were “unfit for self government,” and that it was the duty of the United States to “educate . . . and uplift and Christianize and civilize them.”

Throughout his public remarks and private writings, McKinley’s worldview mixed an imperative to expand American power with the perceived burden of “civilizing” the inferior races that fell within such an expansion. The superiority of White Euro-American culture was always assumed, an assumption that persists today among some Conservative ideologues. Embedded within their talking points are intimations that particular minority groups dilute and pollute a superior White Anglo-American culture that has a duty to perpetuate itself via Manifest Destiny, a very 19th century idea.

Is Trump the new McKinley?

By now, hopefully, it is clear how McKinley’s views of the world inform Trump 2.0.

Like McKinley, Trump and his advisors seem to view the world through the lens of American dominance, with a particular focus on hegemony in the Western Hemisphere. They are not afraid to manipulate the map in order to expand American influence, including an annexation of Greenland, an assertion of rights to the Panama Canal, and a seizure of Gaza. The goal is to expand the markets for American industry, whether that be in the Arctic Circle, the Western Hemisphere, the Middle East or even in Outer Space, a new frontier for resource exploitation and commercial enterprise (asteroid mining, space tourism, etc.). The expansion of American hegemony will boost profits for American corporations and, in theory, create trickle down prosperity for American workers, just as McKinley believed.

Like McKinley, Trump also sees tariffs as a means of shifting the burden of revenue collection from taxation of Americans via an Internal Revenue Service to taxation of foreigners via an External Revenue Service. Trump parrots long-held beliefs inside Libertarian and corporate circles about the evils of domestic taxation. If the federal government slashes its budget and spends trillions of dollars less each year through the elimination of agencies such as USAID and Education—coupled with raising more revenue via tariffs—this would, in theory, substantially curtail or eliminate the taxes paid by American corporations and the American people. It could also realize a long-held dream among Libertarians to eliminate the IRS, which has a very McKinley ring to it. After all, McKinley wrote more than 100 years ago that “direct taxation” would be something the American people “would not stand that long.”

Finally, Trump is a man of grievances, and one of his continual grievances has been that America is taken advantage of by the rest of the world. Trump points to our trade deficits, foreign aid, and spending on the U.N. and NATO as proof points. This also bears a resemblance to McKinley, who sought to use tariffs as a means to balance trade and gain favorable economic advantage for the U.S., as well as ensure that American largesse would not be taken advantage of in the global arena. McKinley was not opposed to cooperating with rival nations on international challenges, for example, sending American troops to China in collaboration with European powers to suppress the Boxer Rebellion. But the pretense was always to act in America’s best economic interest, very narrowly defined through a set of hard power criteria.

All that said, there are substantial differences between Trump and McKinley. As alluded to earlier, McKinley’s legacy has been debated among historians on how imperialist, racist and corporate he truly was. Evidence suggests that McKinley was reluctant to intervene in Cuba until forced to do so by public and media pressure, and that McKinley did have genuine concern for the working class, including being pro-union. McKinley was also a lifelong devout Christian with experience as a Congressman, Governor and President, as opposed to Trump’s career in business and entertainment whose relationships with religious leaders have been largely transactional.

Trump and his inner circle are also not the first Republicans to rediscover McKinley. In the early 2000s, it was reported by several media outlets that Karl Rove, the principal advisor to George W. Bush, had a fascination with McKinley’s presidency. Rove and other Republicans also, reportedly, took note of how Mark Hanna and large donors could sway politics.

Trump has been advised by several Conservative scholars and strategists who are aware of McKinley’s revival. Stephen Miller, Trump’s White House deputy chief of staff for policy, for example, is an avid reader of history as well as an insider within Conservative intellectual circles. It is not a surprise, then, that one of the Trump White House’s first Executive Orders praised McKinley for stewarding America’s “rapid economic growth and prosperity” and his “expansion of territorial gains for the Nation.” It recognized the deceased president’s commitment to “American greatness” and “legacy of protecting America’s interests and generating enormous wealth for all Americans.”

In truth, not all Americans generated enormous wealth in the late 1890s. Black Americans, for example, saw tremendous hardship during the Gilded Age. The year that McKinley was elected also saw the disastrous Plessy v. Ferguson Supreme Court decision that ruled that racial segregation was constitutionally permissible. This ushered in a period of horrific Jim Crow Laws and a Klu Klux Klan revival that oppressed Black Americans for decades. The 1890s was also a terrible decade for Tribal Nations, who were stripped of their land and forced to integrate into White society. Evoking the same language as American imperialism abroad, the government-sponsored “civilizing” techniques at home included Indian Boarding Schools that sought to “Kill the Indian, Save the Man” by erasing tribal languages and cultures. And, certainly, the 1890s were not an era of prosperity for indigenous Hawaiians, Puerto Ricans and Filipinos who found themselves under the thumb of American empire without equal rights as their White counterparts.

What This Means for Trump 2.0

Trump’s foreign policy and trade policy will not hew exactly to those of McKinley. Nor will his actions follow a predictable, historical script; we know that Trump will adapt depending on how the political winds blow.

But his worldview is unlikely to change drastically, and his first few weeks in office, coupled with some historical literacy, offer insights into what that worldview is:

American economic interests will be paramount, backstopped by demonstrations of hard power;

Grievances against perceived slights and injustices will motivate retaliatory tactics, including tariffs;

Expansion of American hegemony and dominance, particularly in the Western Hemisphere will be prioritized;

Expansion of American markets for raw materials and manufactured goods will include the territory of allies, territories of enemies, below the sea floor and into outer space;

The success of American corporations and corporate profits will guide economic policies and international relations, with the expectation that those profits will trickle down to the American worker;

Government spending and regulation will be drastically reduced, with entire agencies eliminated;

An Anglo-American Evangelical ethos will serve as the ideological North Star.

America will likely continue to work with its foreign partners under Trump, but only when a concrete U.S. interest is identified that advances the aforementioned worldview. Ethereal ideals such as preserving democracy around the world, advocating for equality and human rights, and using our wealth and influence for the betterment of all peoples and species on the planet will be de-prioritized, if they are pursued at all.

Will that make for “prosperity at home and prestige abroad,” as McKinley would have said? We will find out. In my humble opinion, it does not make for a stronger and healthier planet that works together to solve societal and ecological issues, but perhaps that is an old-fashioned 20th century notion. Trump seems to have his eyes on the 19th century. History will judge his actions, much like it has McKinley’s.

The second Trump Administration marks a seismic shift in world affairs and is already demanding deep historical knowledge and media literacy to understand it. I feel a responsibility to offer my insights and analysis to help make sense of it, but it will take an extraordinary amount of energy and effort to keep up with the flurry of activity. I cannot do it without your financial support. If you believe that an understanding of history is critical to preserving our democracy, please become a paid subscriber.

Notes

[1] Kevin Phillips, William McKinley: The American Presidents Series: The 25th President, 1897-1901 (Times Books, 2003).

[2] Phillips, William McKinley: The American Presidents Series.

Another banger here Jason. Great context and research. I appreciate your incisive compare and contrast exercise here. I do question one point you made. At the end of the article, you state: "In my humble opinion, it does not make for a stronger and healthier planet that works together to solve societal and ecological issues, but perhaps that is an old-fashioned 20th century notion." Hmmmm... I, for one, do not believe that working together "to solve societal and ecological issues" that produce a "stronger and healthier planet" is on old fashioned idea. In fact, it is the mindset of a noble, moral and wise people. It is our better angels on display for the world to see.

Insightful read as someone who absolutely loathes Trump.

“The tariff—paid for by the foreign entity—also generates revenue for the government... McKinley reasoned that if governments required funding in order to function, that funding must be procured either by taxing American citizens or taxing foreign imports.”

I’ve been under the impression that tariffs are typically paid for by the importer in the country imposing the tariffs. In effect, a tax on the importer inevitably gets passed onto the consumer as an indirect tax, no?