Netflix, Twitter, TikTok & Passover

This year, we are beholden to the algorithms. Next year, will we be free?

Note: Due to a large number of images at the end of this newsletter, Gmail and other inboxes may truncate the message. If you see the words [message clipped] at the bottom of your email, click on the “view the entire message” to read the entire post. -JS

In fall 2015, Netflix CEO Reed Hastings took the stage in New York City and declared confidently that there was “not nearly enough TV.” Less than seven years later, Hastings and his senior leadership team held an earnings call with investors and journalists and admitted there were not enough subscribers for all that television.

Such is the conundrum facing some of our major media companies, whose turmoils have been in the news the past two weeks. The common thread has been not enough users. Netflix estimates it will lose 2 million subscribers. CNN+ folded within one month due to, in part, low subscription numbers. Twitter, which is fending off a takeover from Elon Musk, continues to lag far behind Facebook, Instagram and YouTube after 15 years. Even Facebook lost 500,000 users in the final quarter of 2021.

Where is everyone?

The first answer is TikTok. TikTok has been the fastest growing social media platform of the past few years, with now over 2 billion downloads worldwide. I’ll write a separate newsletter about how TikTok has come to dominate much of modern entertainment—from film and music, to fashion and book publishing—but for now, consider the following: Why should consumers pay monthly subscriptions for video content when they can watch millions of hours of video for free? Why subsidize the salaries of studio executives to make content when users can make their own content? Why have a static experience on a television when users can have an interactive experience on their phones?

The second answer is gaming. We talked about gaming in a previous newsletter, but to restate the point, gaming is currently the largest entertainment industry in the world—larger than Hollywood, television or professional sports. Young people are spending more hours playing video games than previous generations, and media companies are taking notice. Netflix recently acquired game developer Boss Flight entertainment, and Hastings and his team repeatedly mentioned during their earnings call that they are building a team at Netflix to develop interactive and gaming content. The New York Times recently purchased Wordle because it recognized its 1 million+ players were a path to more subscribers. Even Clubhouse has added gaming in order to attract more users.

The third answer is pandemic burnout. The further we get from the lockdown of 2020, the more that period looks like an anomaly. Trapped at home amid existential planetary and political crises, we watched more television; rapaciously consumed news; drove up the stock and crypto markets; and spent countless hours on Zoom, Clubhouse and other applications. As sociologist Manuel Castells once eloquently said, “When we can’t hold hands in the street, we hold hands on the Internet.” Through Clubhouse, Tiger King, CNN and crypto, we held each other’s hands online. But with the pandemic receding (though certainly not over; people are still dying of Covid-19 every day), that moment is proving to be a blip not a trend. Clubhouse has faded in popularity. Fewer people want to be on Zoom. News consumption is down. So called “stay at home” stocks such as Peloton, Roku, Zoom and Netflix are down as much as 65%. And companies such as CNN and Netflix have admitted that the Covid-19 lockdowns deceived them into thinking the abnormal was normal. As Hastings put it, “COVID created a lot of noise on how to read the situation, boosted us a lot in 2020… but now, coming into 2022, that doesn't really hold.”

Netflix, CNN, and Twitter are each still valued at billions of dollars. But as publicly traded companies (CNN is owned by Warner Discovery), they must demonstrate growth. If not, they risk plummeting share prices, unhappy investors, low employee morale and take-overs of the Elon Musk variety. Where will future growth come from? Do these companies need to reinvent themselves in order to attract new users—and retain existing ones? Do they need to pivot to gaming and short-form video in order to stay relevant? Are these cracks in the armor indicative of a bleaker future?

These are questions to which no one knows the answers. But since this is History Club, it is worth pondering the role public historians play in assessing the media landscape and its future. People who speak philosophically about history often cite its lessons. Recent events remind us of an invaluable one: people are often wrong. Even the smartest and most successful individuals are often wrong. Hastings was wrong in 2015 about there never being too much television. (It turns out there can be far too much). CNN executives were wrong about the appetite for CNN+. Twitter’s board has been wrong about growing Twitter’s user base for years—and Elon Musk might be wrong about how to grow Twitter in the years to come. Even the richest and most powerful among us cannot fully predict the future. In 2015, Hastings could not see TikTok coming, nor could he see the rise of gaming, crypto or Covid-19. Likewise, today we cannot see with full clarity what will come next. More wars? Another pandemic? New platforms? The study of history demonstrates how individuals in positions of wealth and power can be wrong with regularity—and the consequences of those wrong decisions for employees, shareholders, consumers and the broader public.

History also demonstrates how those same individuals will often use their positions and status to convince us they are right—often to advance their own self-interests and not the broader public interest. Such is why we need institutions that act in the public interest and that are accountable to forces beyond the stock market and venture capital, institutions such as museums, public libraries, municipal archives, government and higher education. None of these institutions are perfect, and all have been victimized by self-interest and abuses of power. But, as I argue in my book, humility should be history’s greatest lesson. This week, the leaders of Netflix and CNN+ got a dose of it.

A word about diversity: After the “racial reckoning” of 2020, media organizations and tech companies spoke passionately about the need for diversity within their ranks. It was difficult not to notice, then, that in 2022 the major media companies continue to be led by homogeneous teams of executives. The Netflix executives on its earnings call were Reed Hastings, Spence Neumann, Greg Peters, and Ted Sarandos. The past and current executives behind CNN+ were Jeff Zucker, Jason Kilar, Chris Licht, JB Perrette and Andrew Morse, with one female, Alex MacCallum. The battle over Twitter involves Elon Musk, Jack Dorsey, and board members Bret Taylor, Egon Durban, Robert Zoellick, David Rosenblatt, Patrick Pichette and Baronness Martha Lane Fox. (Twitter’s CEO is the Indian-American Parag Agrawal). The paucity of racial and gender diversity has been noticeable, particularly in a post-George Floyd era. Perhaps these companies might have a better pulse on consumer tastes if they had more diverse teams making the decisions?

How this relates to Passover: The subject line of this week’s email invoked the Jewish holiday of Passover, which concluded yesterday. I spent this week in New York with family observing the holiday, which revolves around the themes of slavery and liberation. “We were slaves in Egypt,” we say annually at the Passover Seder, “but now we are free.” We celebrate that freedom by retelling the story of the Exodus, drinking wine, partaking in a ritual feast, and remembering the suffering of both our ancestors and our oppressors. It’s a beautiful tradition, my favorite among the Jewish holidays, and one with applicability to all global struggles for freedom.

But in light of the news this week, another association popped into my head. During the 2010s, journalists wondered aloud about how the changes wrought by social media would affect their industry. In my book, I cited Nick Denton’s 2014 memo to his staff where he wrote, “We—the freest journalists on the planet—were slaves to the Facebook algorithm.” That sentence has lingered in my mind this week. Even when we are free, we can still be slaves. And even when we break free from one set of shackles, we can bind ourselves to another.

Facebook and Twitter’s grips on Internet traffic may be loosening ever-so-slightly. But what is rising in their place? More addictive platforms like TikTok and gaming. I demonstrated in my book how the rush to create history content online sped from Wikipedia, to Facebook, to Twitter, to Instagram, to Clubhouse and now to TikTok and video games. A study of that history shows us how we repeatedly race from platform to platform in hopes of staying relevant, profitable, influential and holding people’s attentions. In repeating that pattern, we cast off one set of shackles only to chain ourselves to another. Before, we were slaves to the Facebook algorithm. Now, we are slaves to the TikTok algorithm. Next year, will we be free?

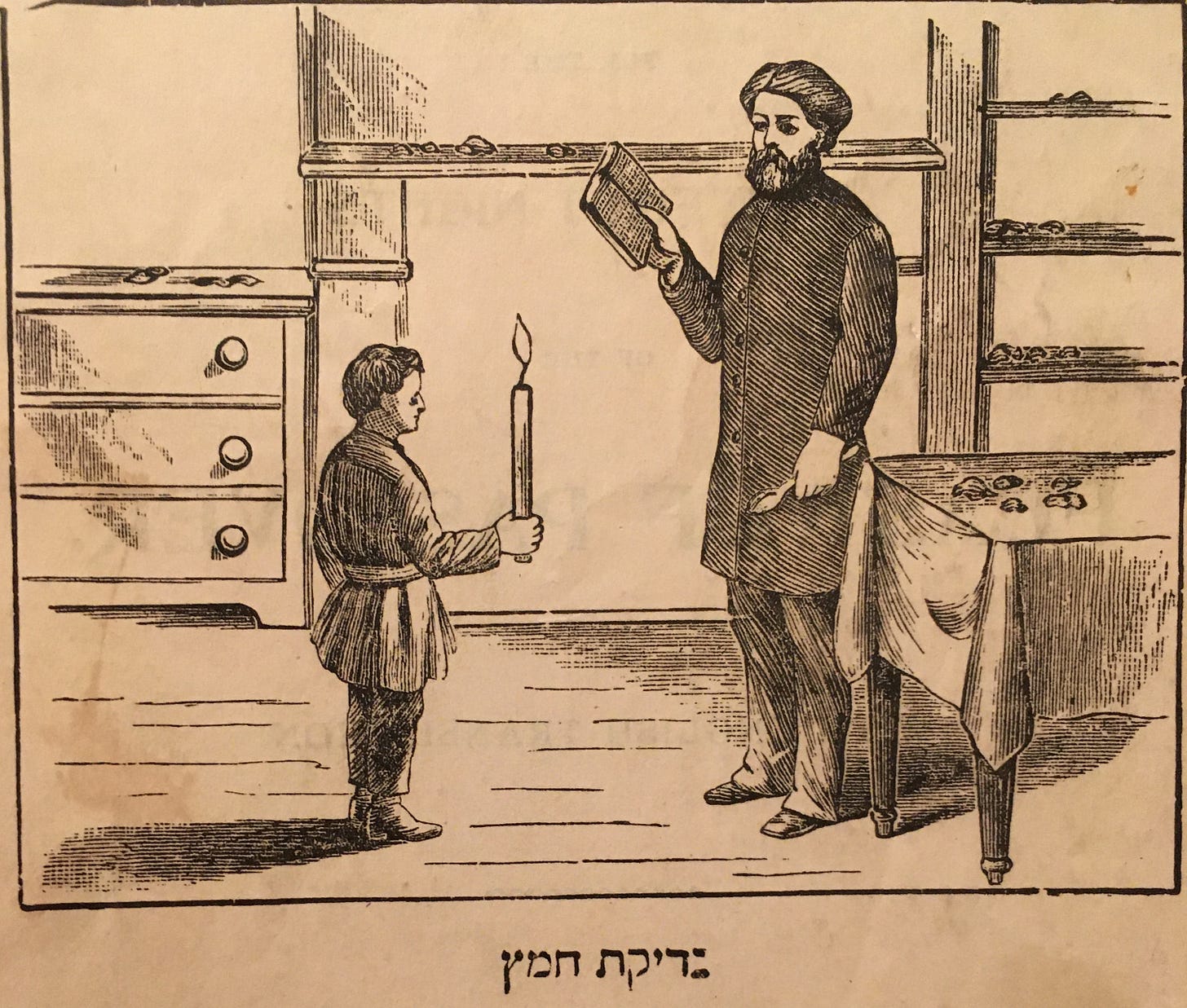

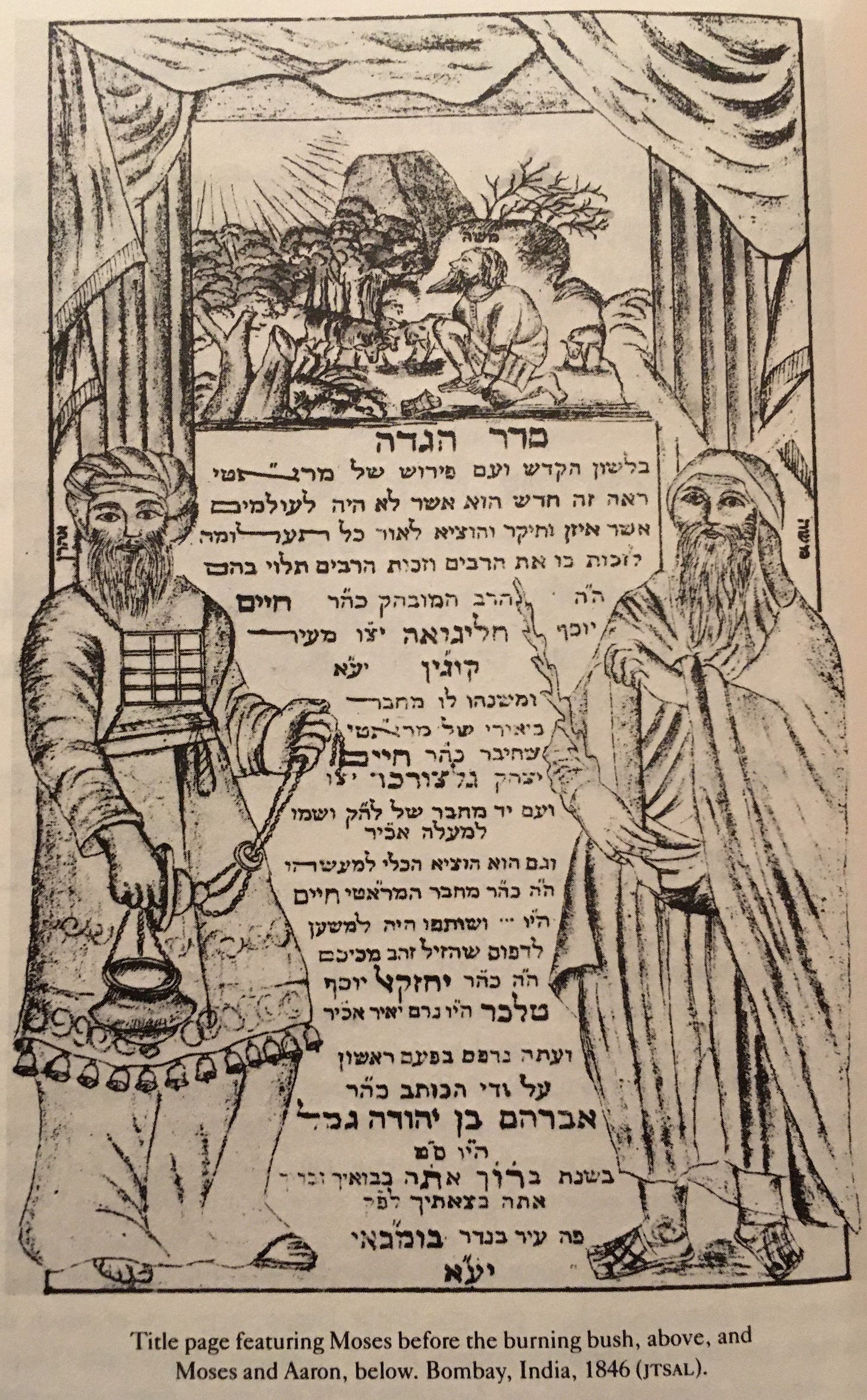

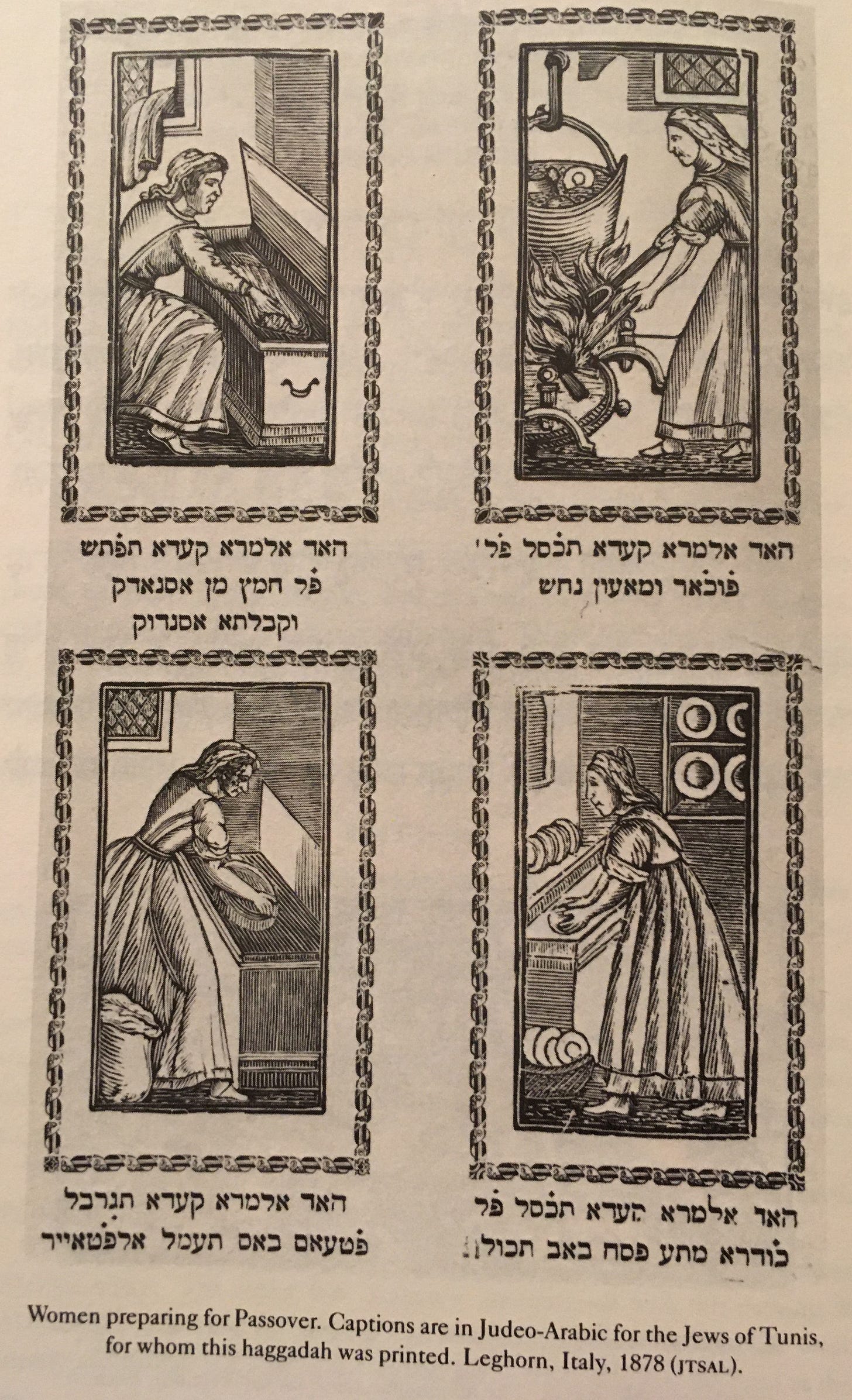

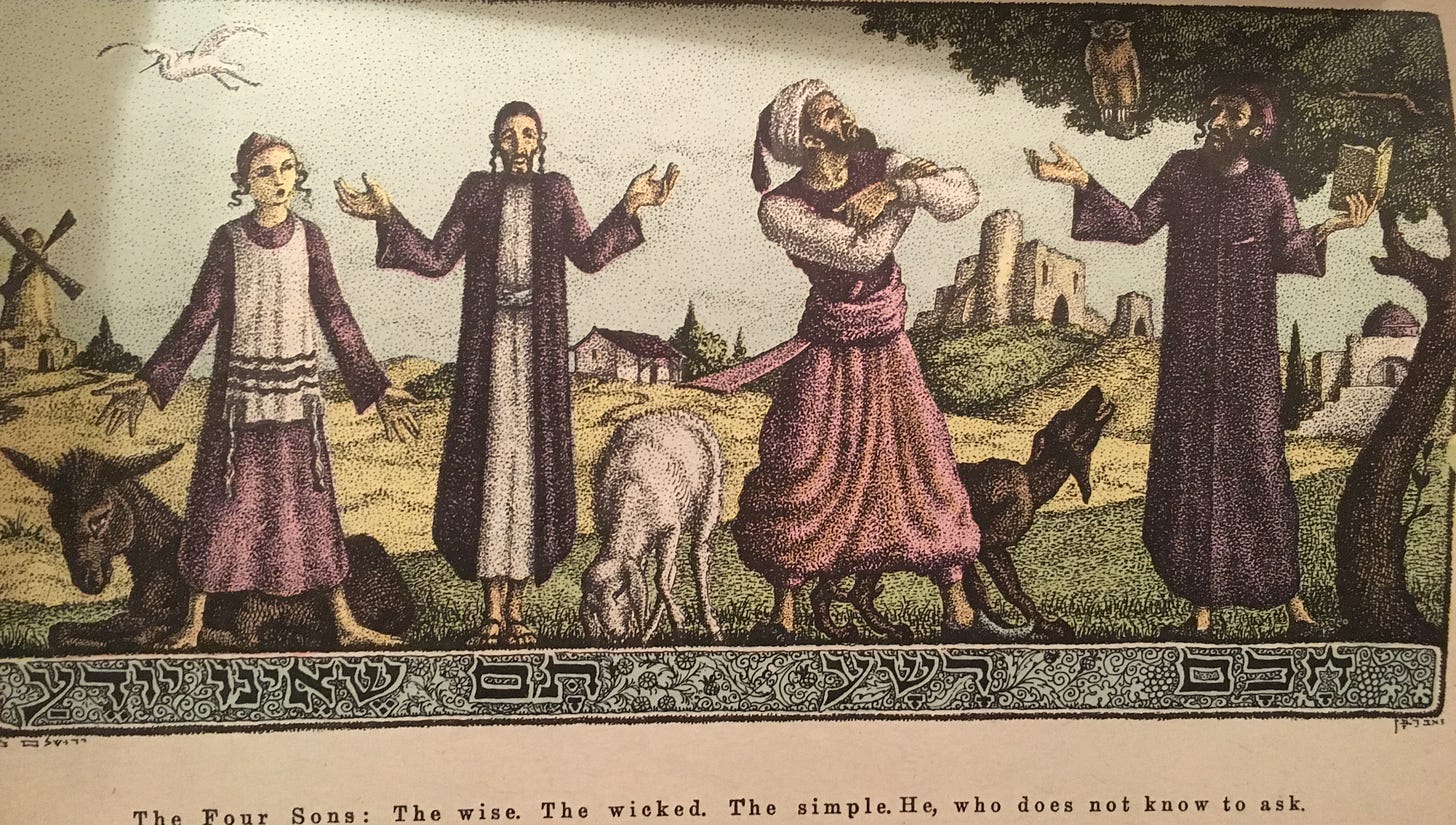

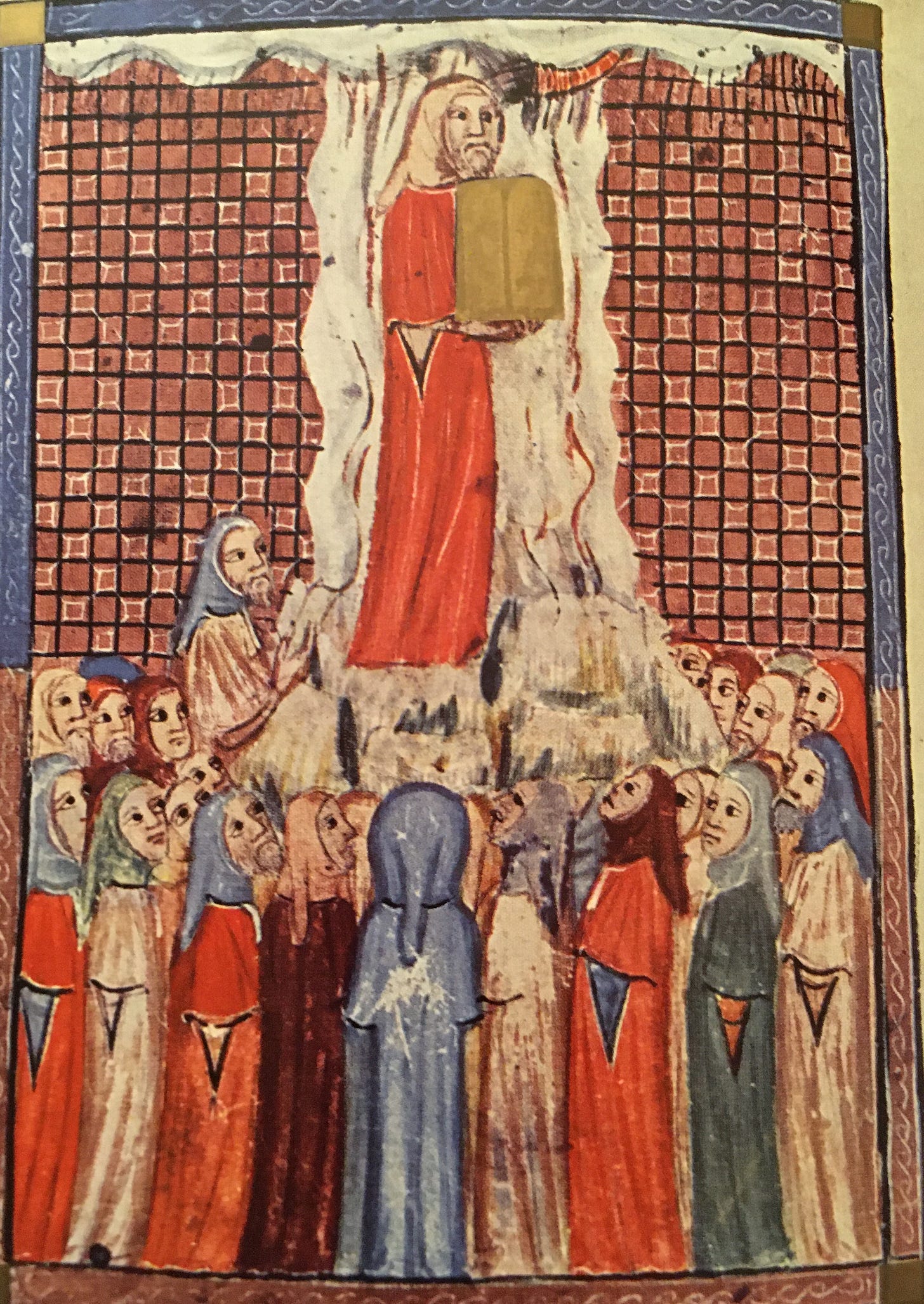

Artwork from the Passover Haggadah: Speaking of Passover, one of my favorite aspects of the holiday is the amazing and diverse artwork found inside the Passover Haggadah. The Haggadah is, essentially, the script that we use to narrate the story of the Exodus and celebrate our freedom. That script has remained remarkably consistent over the centuries, but artists have had many interpretations on how to illustrate it. My parents have a wonderful collection of illustrated Haggadahs, and since I was with them this week, I figured I would share a glimpse into their personal library…

But first! Some links:

The podcast mini-series “Reframing History” continues to release new episodes. Episode 3 and episode 4 are available anywhere you get your podcasts; I’m pleased to be co-hosting with Christy Coleman.

This week I sat down with r/AskHistorians, a community on Reddit with 1.4 million members, to talk about my book History, Disrupted. Listen the conversation here.

On Friday, I delivered the Annual Hewlett Lecture to the Society for History in the Federal Government. Next week, I’ll be speaking with journalism students at the University of Oklahoma (via Zoom) and appearing on the New Books Network podcast. Contact me if you’d like to me to speak with your organization.

Now, onto the artwork:

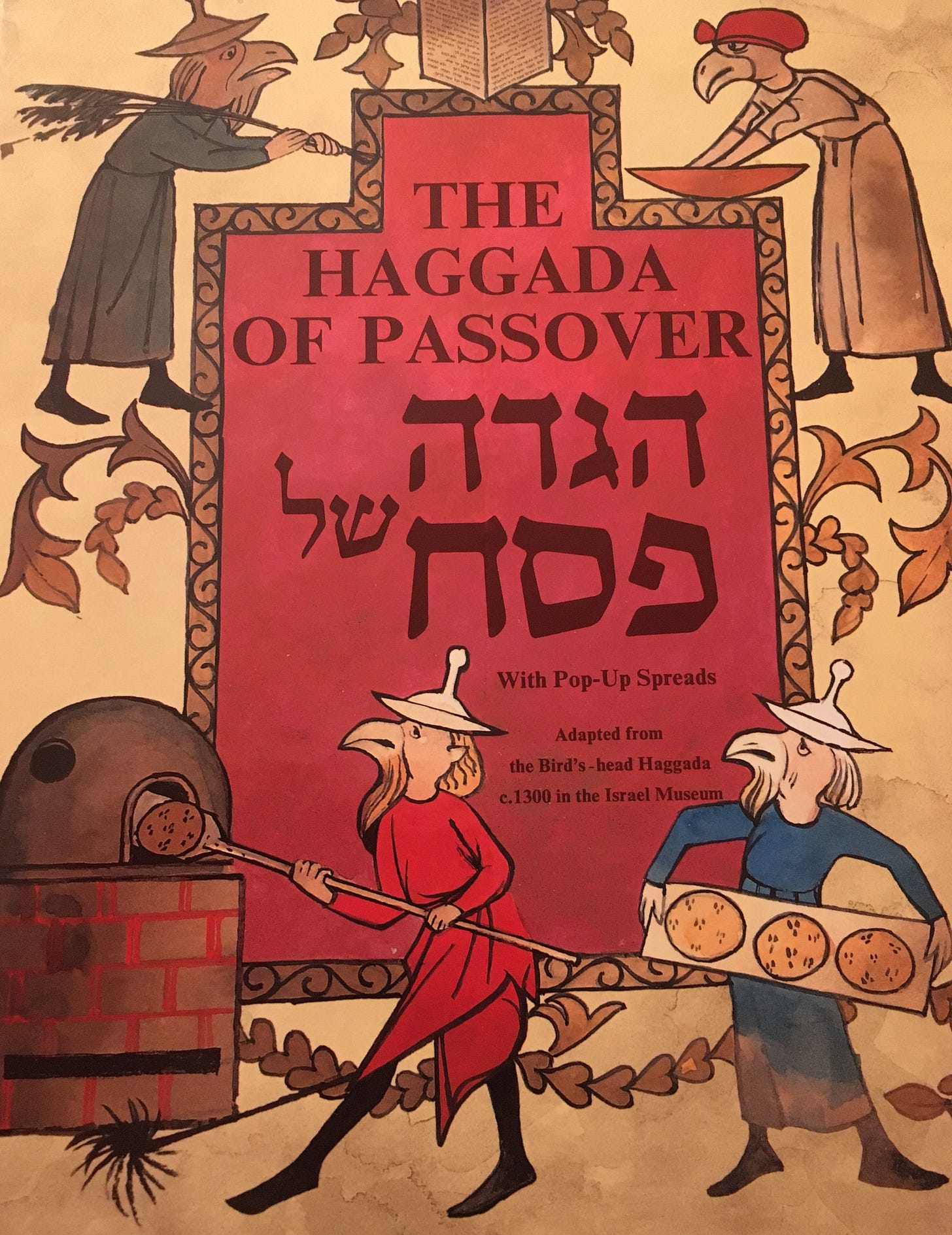

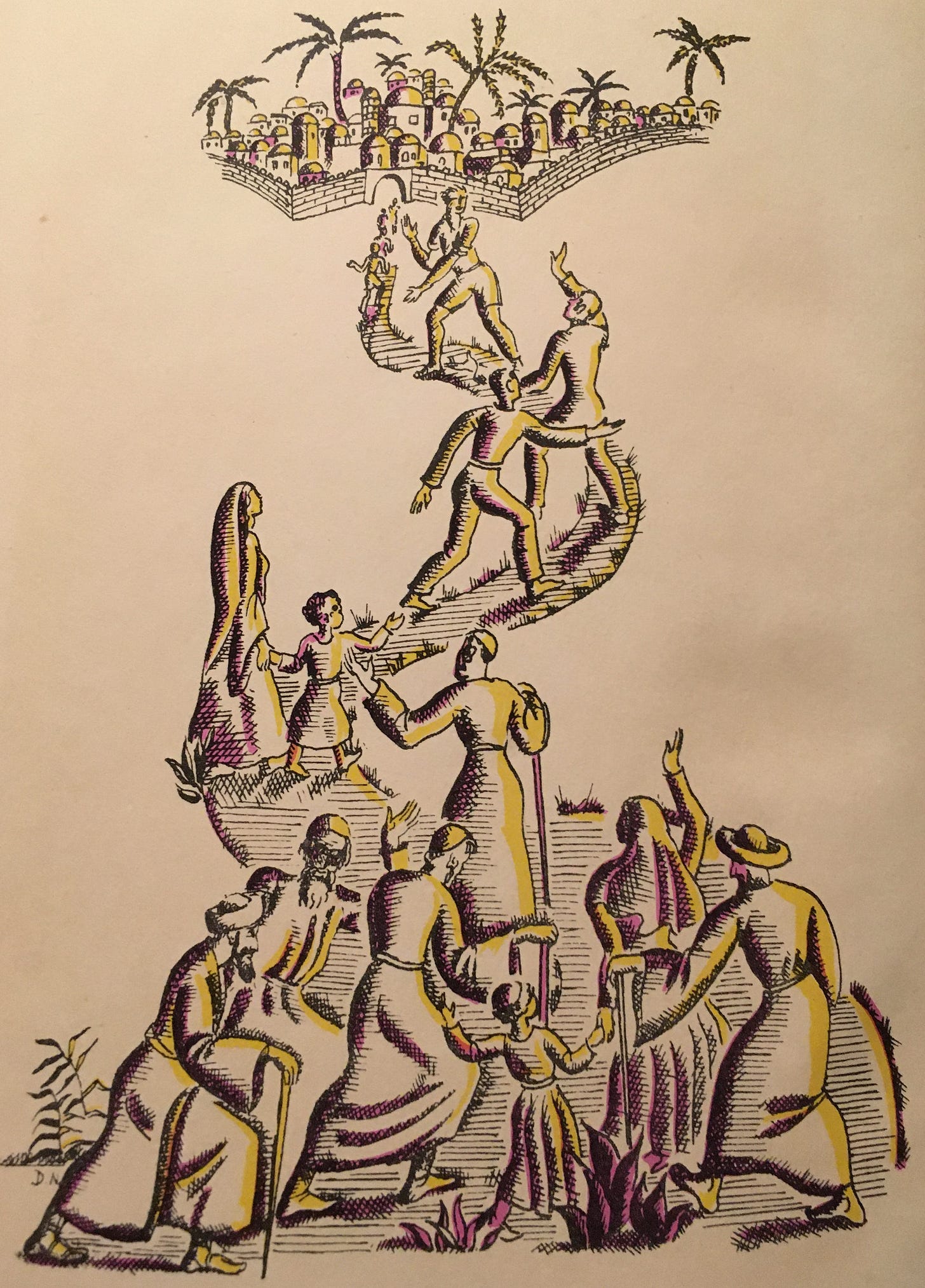

This is a facsimile of the The Birds’ Head Haggadah, now located in the Israel Museum. The original dates to southern Germany ca. 1300, and depicts human figures with birds’ heads. It’s the first illustrated Haggadah known to be created as its own distinct parchment. My parents’ copy includes pop-ups, including this pop-up of Moses and the Israelites crossing the Red Sea.

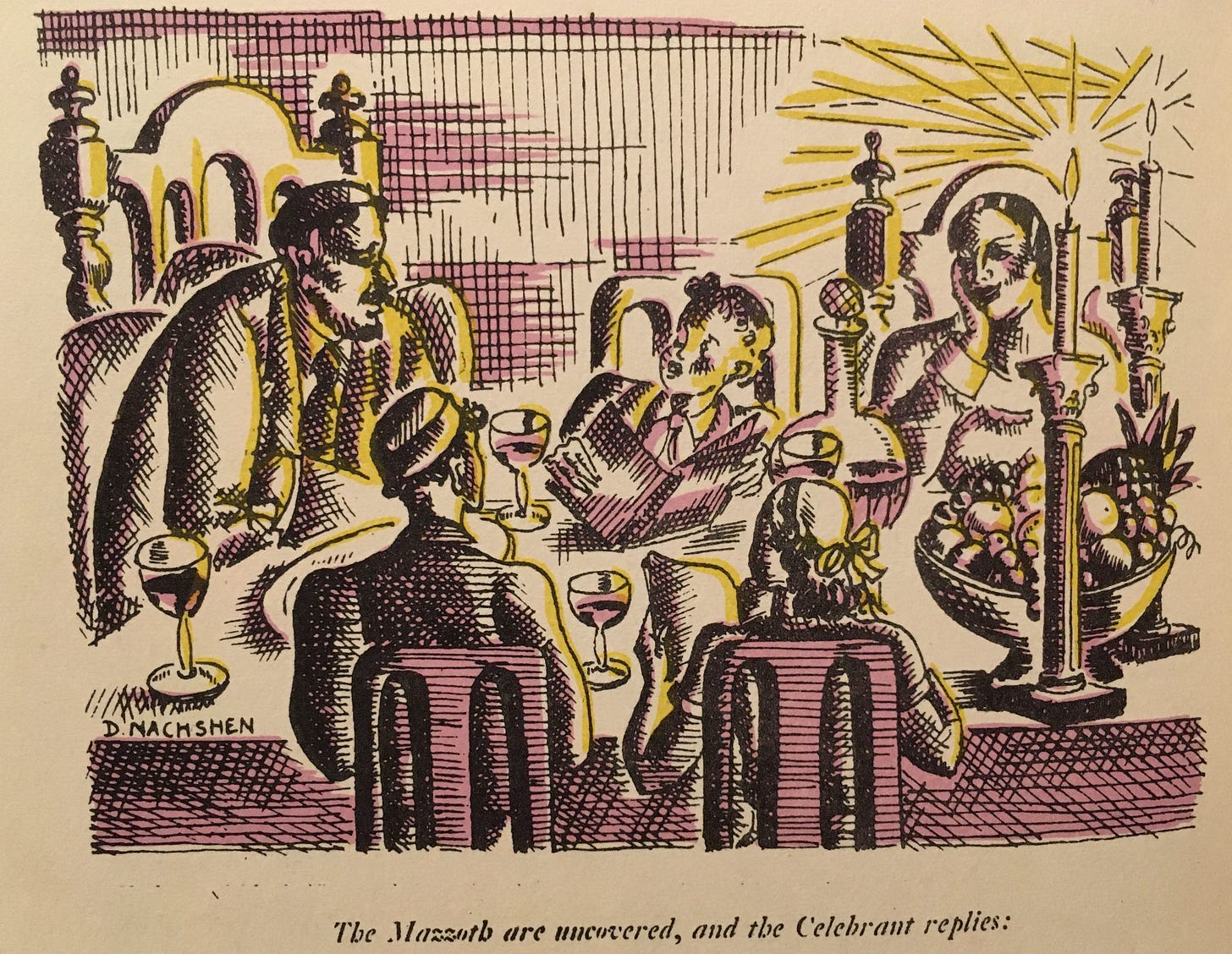

This next Haggadah dates from London, 1934.

This Haggadah was printed on the Lower East Side of Manhattan in 1859.

This is a facsimile of a Haggadah illustrated by Arthur Szyk, who we wrote about in a previous newsletter on countering antisemitism.

This Haggadah features facsimiles of artwork from Bombay, India.

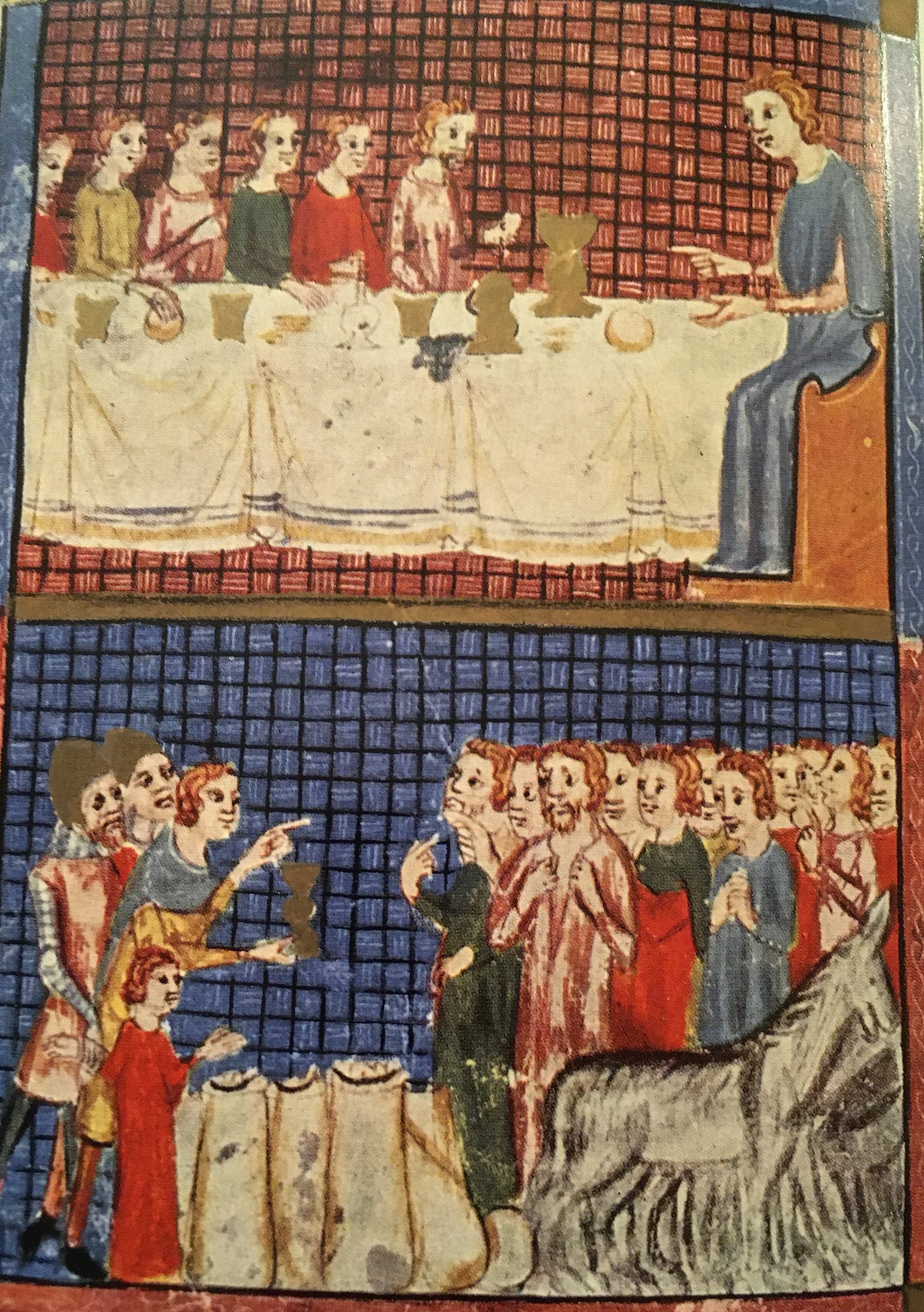

This Haggadah features facsimile artwork from Italy, with captions in Judeo-Arabic and intended for Jews in Tunisia.

This Haggadah was printed in Israel in 1971.

And this is a facsimile of the medieval manuscript known as the Sarajevo Haggadah.

These are just a sample of the thousands of beautiful Haggadahs in existence. Click here and here to see more.

Have a good week.

Part of my cutting back on social media is simply boredom with it. When everyone sees themselves as content creators, too much mediocre content is created. I will be curious whether we "outgrow" social media.