Some thoughts on the European elections

The outcome was predictable; what happens next is far less so

Years ago, I volunteered at the Gay Pride Parade in Washington, D.C. with the Delegation of the European Union to the United States. Colleagues who worked for the EU invited me to help register attendees, hand out water bottles, and march in the back of the column wearing an “EU Loves You” t-shirt. Through a series of unexpected circumstances, I wound up sitting in the passenger seat of the official EU vehicle, waving to the crowds and tossing out souvenirs. For my efforts, I was rewarded with several EU t-shirts and an EU hat.

I’ve worn the EU hat ever since as part of my rotation of baseball caps. (As a bald man, hats are crucial to my wardrobe.) On my recent trip to Germany, which I’ll write about in a future newsletter, I brought my EU hat along, thinking that with the European Parliament elections coming up it would serve as a visual reminder to vote and a means to keep the summer sun off my scalp. I wore it so much that I often forgot I had it on—except for one afternoon in Berlin. While walking down Oranienburger Str. towards Hackescher Market, a man saw my hat, growled in a language I did not recognize, and spat on me. He then walked away, and I, being with a colleague and not seeking any trouble, wiped my hat clean and continued on my path.

Given the results of the EU elections, which became clear over the past week, one might be tempted to see this encounter as a metaphor. The so-called “Euro-skeptics”—those who might proverbially spit on the European project—surpassed expectations, gaining seats in parliament. In France, the EU’s second largest economy and its sole nuclear power, the party led by EU stalwart Emmanuel Macron lost by nearly 2-to-1 to the National Rally party led by Marine Le Pen. The results induced Macron to call for a snap election, which will begin on June 30. In Germany, the EU’s largest economy, the ruling coalition was equally humbled, finishing with a smaller percentage of the vote than the scandal-plagued Alternative for Germany (AfD).

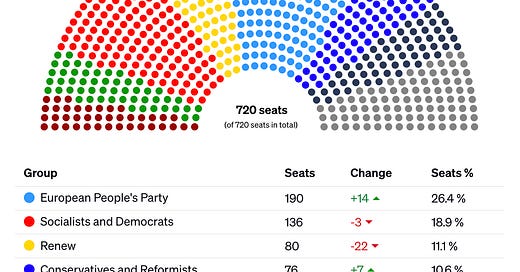

European politics are complex, and readers, particularly in the U.S., may not be well-versed on which parties in which countries represent which constituencies. At a very broad level, each of the 27 countries within the European Union sends a certain number of representatives to the European Parliament (EP), which is the EU’s only body elected by its citizens. Every five years, each country holds elections for its EP representatives, and the winning parties align with broader coalitions that are Europe-wide. For example, Germany holds 96 seats in the EP, and in this election the Christian Democratic Union won 30% of the vote (29 seats); the Alternative for Germany won 16% (15 seats); the Social Democrats won 14% (14 seats); The Greens won 12% (12 seats); and an array of smaller parties won single digit numbers of seats. These parties will align with larger groups once they get to Brussels: the Christian Democrats will align with the European People’s Party, the Social Democrats will align with the Socialists and Democrats, etc. As these alignments play out across the 27 EU member states, the composition of the European Parliament takes shape.

One major storyline for the incoming parliament has been its marked shift to the right—in some cases, the far-right. The European People’s Party, Conservatives and Reformists, and Identity and Democracy all skew right politically, and the Nonaligned faction includes Alternative for Germany and Fidesz, the ruling party of Hungary led by Viktor Orban, which are categorized as far-right. In Germany, France, Italy, Belgium, the Netherlands, Austria, and Hungary conservative parties with nationalist and populist tendencies had strong showings. These factions gained representation while left-leaning parties such as the Greens, Socialists and Democrats, and Renew Europe lost representation in many (but not all) regions.

Why did this happen? The results are not a surprise; many polls predicted them, and in this newsletter I wrote in 2022, 2023 and 2024 about the forces gathering energy across Europe that foretold of such an outcome. Since the COVID-19 pandemic, Europe has become increasingly fractured and discontented, in part organically and in part instigated by societal actors with such purposes in mind. As someone who has worked extensively in Europe the past three years, the discontent has been evident in every place I’ve traveled. While it manifests differently in different countries based on historical and cultural factors, if I was asked to summarize in one word what I have sensed in Europe’s current political moment, I would use the word “instability.”

Instability has been the principal emotion I have encountered during my European visits, a sentiment I have chronicled over several years of articles. The instability has many causes, including climate change, inflation, the pandemic, immigration, unemployment and the war in Ukraine. In countries such as Finland, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, the Russian invasion has ratcheted up anxieties about whether they, too, might be in Russia’s crosshairs. In countries such as the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, and Germany, inflation rates have sometimes exceeded 10% during the past few years, placing major strains on housing, fuel, food and quality of life. In countries such as Spain and Greece, unemployment stubbornly hovers at-or-above 10%, and in North Macedonia (which is not yet in the EU), the unemployment rate is 15% with youth unemployment above 35%. Students across the continent have asked me how they will find work in the future if artificial intelligence makes human labor unnecessary. Meanwhile, several European countries lead the world in negative population growth, as low birth rates coupled with an exodus of college graduates leave Bulgaria, Serbia, Bosnia and Albania investing in the education of their youth only to watch them depart as adults. At the same time, immigrants from Africa and the Middle East have arrived in large numbers across the continent, resulting in major clashes among racial and religious lines, as well as waves of bigotry and discrimination. All of this is exacerbated by climate change, which this century has produced five of Europe’s hottest summers since 1500, killed tens-of-thousands of people, and caused cataclysmic droughts and wildfires.

The current EU leadership has struggled to find solutions to these challenges that resonate with the broader public—in part because these problems are so complex and decades in the making that few, if any, policymakers have the means to reverse them in a span of an election cycle. Despite inflation easing in the Eurozone, the shocks of high prices have left scars on European laborers. Many parents worry their children will be worse off as technology changes the workplace faster than the workforce can be prepared for it. Climate change mitigation tactics that penalize farmers have made agricultural workers feel unfairly scapegoated and they, in response, have mobilized large protests backed by populist politicians. Tensions over immigration remain unresolved, which in a period of high inflation, high unemployment, and anxiety over rapidly-changing technology makes an influx of new labor even more threatening to local populations. And while the EU has largely remained united in its support of Ukraine, more than two years into the Russian full-scale invasion segments of the European public are losing faith that Russia can be defeated on the battlefield and that Europe can sustain billions of dollars in aid for Ukraine each year.

In any election, citizens are offered a referendum on the ruling classes, and when there is discontent with the status quo it manifests at the ballot box. Those who promise change and disruption always seem appealing in moments of paralysis. Such was the case here. But more fundamentally, in a period of broad uncertainty it stands to reason that citizens will seek a feeling of stability that comes from looking backward, as opposed to forward: back to a time when prices were lower, fewer immigrants arrived, and there were more job opportunities. These nostalgic emotions have been omnipresent in my European travels. From nostalgia for the Tito dictatorship in the Balkans, to nostalgia for the communist East Germany, to the longing for the restoration of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, nostalgia has been a consistent response to a period of mass instability, exploited by populists seeking power. The desire to close borders, expel migrants, and enforce ethno-nationalist boundaries becomes more appealing in such an environment. Closed borders and strongly delineated ethnic identities promise a sense of control over one’s destiny that feels lacking amid a large European bureaucracy struggling with existential threats. Indeed, that promise of control over destiny is central to far-right messaging (it also catalyzed Brexit in 2016), the desire to take power away from Brussels and place it in the hands of countries defined along strict ethnic and religious lines. Nationalism, closed borders and disinformation offer tidy solutions for complex problems, all evident in post-Covid Europe.

What, then, will be the effects of this year’s elections? Some commentators have suggested they may weaken the EU’s commitment to tackling climate change. Others have suggested this may dampen the EU support for Ukraine. Perhaps this will even signal the end of the European Union as we know it? After all, officials from Belgium’s Vlaams Belang, Germany’s Alternative für Deutschland, and Austria’s Freedom Party are on the record as stating that the Treaty of Maastricht that forged the modern EU was “wrong” and its anniversary was a day to “mourn.”

In the short-term, however, these elections may have a more iterative effect, as opposed to a seismic one. The European Parliament is not the sole arbiter of Europe’s direction. The European Commission, which is the EU’s executive branch, plays an important role in the management and execution of EU policies, as does the Council of the European Union (each country rotates leading the council; currently it is Belgium, next it will be Hungary). These transformational processes are often long-developing; the instability across Europe has grown over years and decades, as has the political strength of the far-right. The next question is whether that growing strength will manifest in country-wide elections, the first test being France in a few weeks.

When I was in Brussels in March, I received a tour of the House of European History (another subject for a future newsletter). That museum does a compelling job of reminding visitors that Europe has, for three centuries, been a hotbed of revolutions, whether it be 1848 or 1989. In 1848 in particular, liberals across Europe sensed an opportunity for political transformation. But in the end, conservative forces won and the liberal revolutions of 1848 were defeated. As scholar Michael Rapport has written, “the liberals themselves, forced to choose between their own libertarian principles and the restoration of order, generally opted for the latter.” In Europe today, the liberal principles of fighting climate change, embracing immigration and expanding the definition of what it means to be European have collided with the realities of popular desires for order, stability, tradition and control. The revolution in this instance has come from the right, in the form of farmers in the streets and voters at the ballot box. Will that revolution succeed in halting the advances of liberal reforms? Even for those of us who have engaged with Europe closely, no-one yet has a definitive answer to that question.

Happy Father’s Day to all the dads around the world,

-JS

So well written and clear.