I’ll never forget the first time I crossed the Mississippi River by car. We were in our mid-20’s, on a cross-country road trip, and amid a driving rain storm we traversed the mighty Mississippi at the Wisconsin-Minnesota border, then took refuge in a motel in Albert Lea, Minnesota. It had rained the entire way from New York, but when we awoke the next morning and got back on I-90, it was as if God had cast a bright blue rainbow across our windshield. The sun shone, the hills rolled, and before our eyes were wide stretches of fields and skies that wowed us East Coast city-slickers.

South Dakota was the biggest surprise of that trip. We had no idea what to expect—neither of us had been before—but it was simultaneously beautiful and bewildering. More than 400 miles wide, and six hours by car from end-to-end, along the highway we saw scenic vistas, big skies, quirky attractions, yapping prairie dogs, and copious signs for Wall Drug, a general store in Wall, South Dakota, that may be the most infamous tourist trap in the U.S. Passing through Sioux Falls, Mitchell, Rapid City, Deadwood, the Badlands and the Black Hills, the landscape grew more and more alien, and the burdens of history became heavier and heavier. We learned that so many travelers—people and animals—had passed through these plains and wilderness over thousands of years, searching for home, land, food and treasure. We were simply temporary sojourners amid a long and vast migration story.

Archaeologists can now date that story to more than 12,000 years ago. Back then, fantastic mammoths, camels and sabertooth tigers roamed our continent. The so-called Clovis peoples traveled across the lands hunting these mega-mammals. The current thinking is that climate change, coupled with an asteroid that hit Canada, wiped out the large animals that helped sustain the Clovis, who were succeeded by Folsom hunter-gatherers who circled the Great Plains, Rocky Mountains and American Southwest. The Folsom subsisted by following great herds of giant bison that grew as high as 14 feet tall. Over centuries the Folsom gave way to the Plains Archaic hunters, who gave way to the Woodland peoples, who were followed by the Middle Missouri farmers and the Coalescents. They were the ancestors to the Arikaras and the Mandans, who traded with the Crows, Cheyennes and Pawnees. Eventually they were all pushed north and west by the Dakota, Lakota and Nakota (Sioux) peoples.

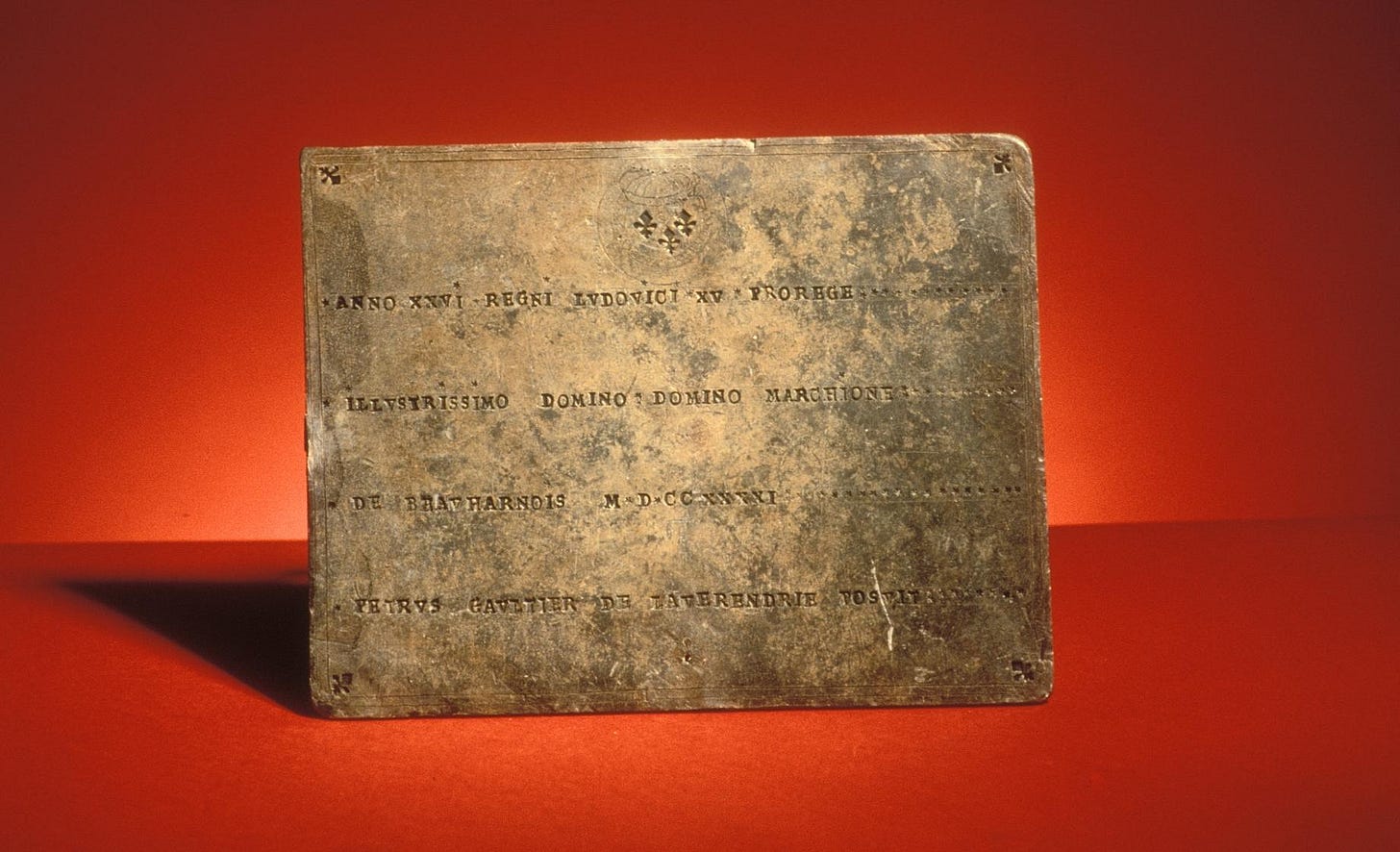

The first Europeans in South Dakota were French. In 1743, Francoise La Verendrye and his brother, Louis-Joseph, arrived from Canada looking for a trade route that would connect North America to the Pacific Ocean, a so-called “Northwest Passage.” They encountered the Arikara and Mandan along their journey, and unable to find the passage, on their way home placed a lead tablet on a hill near the Missouri River “claiming” the area for France. The Verendrye brothers were traders and described the landscape as full of “magnificent prairies where wild animals were plentiful.” Specifically they sought beaver fur, which at the time was woven into valuable and fashionable hats. They were not the only ones.

Soon, more Europeans arrived. Pierre Dorion, a French-Canadian, came to South Dakota in 1785. He married a Nakota woman, and they lived along the Missouri River near what is now the city of Yankton. British traders came up the Missouri River, making it as far as the Mandan villages in North Dakota. As for the lead plate, the La Verendrye brothers marked it with a pyramid of stones, but the stones fell over and the tablet was hidden for 170 years. Then, in 1913, three high school students stumbled over it in the town of Fort Pierre, just across the river from the South Dakota capital of Pierre. That was the location of this year’s annual state history conference, where I was the keynote speaker.

Pronounced “peer”—as opposed to “Pee-air”—Pierre is the second smallest state capital in the U.S. (the first is Montpelier, Vermont). This peculiar piece of trivia was relayed to me by my host, Dr. Benjamin Jones, the state historian, who picked me up at the airport upon my arrival. Pierre Regional Airport had one gate and was accessible via tiny airplanes flying from Denver under the moniker of the Denver Air Connection. From the East Coast it was a full day of travel; like in so many centuries prior, the journey west to the South Dakota plains was a long and adventurous one.

Jones earned his Ph.D. in History from the University of Kansas, and served 23 years in the U.S. Air Force. Along the way, he authored a book about the American liberation of France during World War II. After serving as dean at Dakota State University, he was tapped to be South Dakota’s Secretary of Education before being appointed as the state’s chief historian. (He is also a podcast host; he interviewed me about History, Disrupted, which is how we met.) As if his historian bona fides were not already strong enough, when he picked me up from the airport, Ben was listening to a re-airing of a radio broadcast from the 1967 World Series. With Bob Gibson on the mound and the crackling voice of Harry Caray in the background, we drove through the South Dakota dusk, past the State Historical Society (currently under renovation), through the rolling bluffs and into downtown Pierre. Ben dropped me off at the vintage Ramkota Hotel, our home base for the conference nestled on the banks of the Missouri River. “Just across the bridge is Fort Pierre,” he said with a grin, “and the spot where the French marked the land in the name of Louis XV.”

Present-day Pierre belies these mythic histories. Downtown has numerous abandoned store fronts, and according to census data, the city has a 12 percent poverty rate and a per capita income of under $40,000. Only a third of the population has a college degree, and 8 percent have no health insurance. It is more than 80 percent White, with 10 percent American Indian or Alaska Native. State-wide, South Dakota is home to nine sovereign nations:

1. Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe,

2. Crow Creek Sioux Tribe,

3. Flandreau Santee Sioux Tribe,

4. Lower Brule Sioux Tribe,

5. Oglala Sioux Tribe,

6. Rosebud Sioux Tribe,

7. Sisseton Wahpeton Sioux Tribe,

8. Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, and

9. Yankton Sioux Tribe.

These nine reservations cover about 5 million acres, and are home to more than 75,000 people. However, poverty rates on the reservations far exceed national averages, according to local press reports. The poverty rate on the Cheyenne River Reservation is 43 percent. The poverty level at Pine Ridge is 54 percent. In Oglala County, 52 percent of the population live below the poverty line. American Indians and Alaska Natives have a lower life expectancy in South Dakota than their White counterparts, and are dying at higher rates than other Americans in many categories, including cirrhosis, diabetes, homicide, suicide, and chronic lower respiratory diseases, according to the Indian Health Services.

Such disparities between White Americans and Tribal Nations make South Dakota’s choppy rivers of history even more complex to navigate. At the conference, we listened to a presentation by Seven Generations Architecture and Engineering, an indigenous-led firm that is developing the site of the former Rapid City Indian Boarding School in Rapid City, S.D. Readers may be aware that in the 19th century, the U.S. federal government created a series of boarding schools to “assimilate” Native American children. There were several in South Dakota, including the school in Rapid City, which opened in 1898. Native children were separated from their families and forced into an American/European style education, the rationale being that stripping them of their indigenous culture would enable their integration into American life and further eradicate Native populations. Conditions at the schools were poor, and included beatings by headmasters and diseases such as tuberculosis. At least 50 children and infants passed away at the Rapid City school (the true number is likely far higher), and others died trying to escape. In 1909, Paul Loves War and Henry Bull lost their lower legs to frostbite after trying to escape the school in the dead of winter. In 1910, James Means and Mark Sherman died when they were struck by a train as they slept on the tracks.

The Indian Boarding School closed in 1933, after which it became a segregated tuberculosis clinic that operated into the 1960s. Today, the location is known as the “Sioux Sanatorium” site and is run by the Indian Health Service (IHS). A memorial to the horrors that occurred is in development, and Seven Generations A+E is working with the IHS to build a new 40-acre Oyate Health Center for tribal communities that will incorporate both traditional healing and modern medicine. The remains of the old structures are being woven into the design, as required by federal law under Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act.

My keynote speech followed this presentation. Unbeknownst to me prior to my arrival, my lecture had been made possible by a generous donor named Verna Kay Bormann. Now in her mid-70s, Verna had a long career in the healthcare industry, and upon retirement realized that she had a love of history and wanted to see historical work in South Dakota continue. She made a donation to the South Dakota Historical Society to fund a new publication series and an array of programs, including my talk.

Verna Kay and I were seated at the same table, and we spent several minutes laughing and talking before my speech began. She grew up in South Dakota and Minnesota, traveling to the East Coast only a few times in her life. She had been to New York, but was not a big fan of it, finding it too dirty and too crowded (it was hard to argue with her on either point). She preferred South Dakota, where she could see the sky, and now lived in retirement caring for her brother and wondering what type of world we were leaving behind for future generations. Before she introduced me at the podium, she told the audience that she had never been to a history conference before, but that she was having so much fun at this one she would certainly be attending more.

Once my talk concluded, awards were handed out to several attendees, including JoAnne Bohl, a social studies teacher from Hartford, South Dakota (population 3,354), who was awarded history teacher of the year. JoAnne and I spoke once the conference ended, lamenting the current state of history education. She told me that in some parts of South Dakota, students get one hour of social studies per week. The focus is almost entirely on S.T.E.M.—science, technology, engineering and math. This has been a recurring pattern in my travels across the U.S. and Europe, where teachers and librarians at the high school and elementary school levels tell me how history and social studies are being hollowed out by their school districts. What kind of citizenry are we creating if students know nothing about the past, nor have any awareness of prior interactions among diverse societies? To have an information literate and historically literate citizenry requires that we not outsource our knowledge of the past to machines and social media, which is the central thesis of History, Disrupted.

Mine was a quick visit—only two days—and between that and my prior cross-country trip, I’ve spent less than a week in South Dakota. But, the state has left an impression. Standing on the banks of the Missouri River, the landscape has the power to stir the soul. One can imagine thousands of years of people and animals following the river and the stars in search of food, shelter and passage.

On my flight home, I thought about what the Ancient One in the Marvel movie Doctor Strange says to the title character to humble him: “Who are you in this vast multiverse?” Who am I in this vast and complicated story of peoples and civilizations who have passed through South Dakota and left small pieces of evidence behind—a tablet buried in the ground by two French brothers, or a Winter Count left by a Nakota Indian documenting year-after-year of long, hard seasons. The bluffs and plains hold many secrets that will never be unearthed, grand stories of complex interactions among animals and peoples, cultures and religions—some that resulted in peace and others that ended in destruction. We understand only a tiny portion of that complexity, a humbling reminder in a world where byte-sized packets of sophistry on social media are routinely passed off as wisdom. A thorough understanding of the past cannot be wedged into a single tweet or one hour per week of social studies. It would take a lifetime—and not even then—to fully unpack the meaning and significance of a place such as South Dakota, let alone the United States or the broader world.

Fortunately, because of people like Ben Jones, Verna Kay Bormann, JoAnne Bohl and others, that work continues—at least for now. Will it be memorialized and passed down… or will it be buried in the ground and forgotten? That is a question we all must ponder as we seek to build a better world.

Have a good week.

-JS

P.S. - South Dakota Public Broadcasting was kind enough to interview me in connection with my visit. You can listen to that interview by clicking on the thumbnail below.

Interesting essay, as always, and replete with lots of history.

It is not just history that is being 'buried' by our educational systems, but all liberal arts programs in favor of STEM. So, we will have people with great intelligence in STEM subjects but unable to compose an essay.