The case for public diplomacy

As democracy faces more challenges, our relationships around the world become more important

Earlier this year, something very cool happened that I never had the chance to write about: my passport was accepted into the State Department museum.

For those unaware, deep in the Foggy Bottom neighborhood of Washington, D.C., on the grounds of the U.S. Department of State, resides a museum dedicated to American diplomacy, called the National Museum of American Diplomacy.

The museum features artifacts from Secretary of State Madeleine Albright; objects from Foreign Service Officers stationed in Berlin during the Cold War; and stories of notable diplomats such as Raymond Telles, America’s first Hispanic-American ambassador.

Now, among that collection, is my expired passport. The passport, along with copies of my personal photographs, commemorate my work with the State Department in the realm of public diplomacy and citizen diplomacy. Totaling 12 countries across 14 missions to-date—plus numerous engagements here in the U.S.—I have made a very small contribution to American diplomacy compared to career foreign service and civil service officers. But the museum was kind enough to recognize these contributions, and one day, perhaps, my children and grandchildren will be able to see in the museum a glimpse of how I worked on behalf of my country to try and make a better world.

Why bring this up now? As the current administration makes way for the new one, I can’t help but wonder how the State Department may change in the years ahead.

After all, during the previous Trump Administration, the Department of State was targeted for funding cuts and staff attrition. The Trump White House proposed cutting the State Department by 31 percent in its first year, and many positions remained vacant throughout the four-year term. I recall having coffee in 2018 with a foreign diplomat who told me that she, literally, had no one to call at the State Department. All of the people she’d worked with were gone, and all their positions were empty.

For those who want to see America go it alone, perhaps reducing our diplomatic footprint makes sense. But for those of us who believe the United States needs to build relationships around the world in order to tackle global challenges—and continually invest in those relationships year after year—decimating the State Department seems like a short-sighted policy choice. Building and maintaining relationships takes time, effort and, most importantly, people. When positions are vacant or disappear, our allies (and adversaries) have no one to communicate with, no one to share intelligence with, and no partners to collaborate with. Personally, I don’t see how that benefits the United States or the rest of the world.

But what exactly does the State Department do? What do “public diplomacy” and “citizen diplomacy” even mean? How does this work help the U.S. and the wider world? Allow me to use this week’s newsletter to share some reflections on these questions through the lens of my own experiences.

(Note: this is a long read. For those who want to skip to the end, there is a call-to-action to support a personal project I want to launch in 2025 related to citizen diplomacy. Fast-forward to the bottom to learn how you can help).

I should clarify that I do not work for the U.S. Department of State (DOS), nor have I ever been a DOS employee. It would be interesting to work at the State Department, but that is a conversation for another time.

I should also, briefly, explain the terms “public diplomacy” and “citizen diplomacy” – from my own point of view, not as any representative of the U.S. government.

Diplomacy is the art and practice of interacting and negotiating between and among nations. Those interactions usually happen from one government official to another (e.g., ambassadors from two countries holding a meeting) or from government officials to civilians (e.g., passport or visa services at a consulate or embassy).

But occasionally private citizens do diplomatic work with, or on behalf, of their countries. That’s what I do. I’m an independent citizen who speaks and writes on his own behalf, and I collaborate with the State Department on short-term contracts and/or speaking engagements that work to advance America’s broader diplomatic goals. It’s diplomatic work—building bridges between the U.S. and the wider world—but my point of view is my own.

The work falls under the broad umbrella of “public diplomacy.” Without getting too much into the weeds (USC Annenberg has a robust definition for those interested), the ideas behind public diplomacy are: (1) We can speak directly with foreign audiences—whether it be journalists, government officials, academics or students—to explain our views on world affairs and where we stand on important issues; (2) We can build partnerships with foreign organizations in order to achieve common goals; and (3) We can use public programs to build goodwill and lasting relationships.

There are more cynical views on public diplomacy; i.e., that it is, essentially, a branding exercise that countries undertake to improve their image. That is not how I view it; my goals are to exchange ideas, forge relationships, understand the dynamics playing out on the ground, figure out where we can help, and, most importantly, model and embody what I believe our values should be: democracy, equality, human rights, honest and accurate history, media literacy, critical inquiry and positive change.

I’ve been fortunate to do this in 12 countries on 14 assignments to-date:

Lithuania

France

Belgium (twice)

Georgia

Germany (twice)

Bulgaria

North Macedonia

Hungary

Estonia

Latvia

Kosovo

Romania

I’ve also three times presented to foreign visitors participating in the State Department’s International Visitor Leadership Program (Eastern Europe, Southeastern Europe, and Malaysia); twice worked with the European Digital Diplomacy Exchange; and been part of the U.S. delegation to the international Conference on Holocaust Distortion and Education. Long-time subscribers to this newsletter, or followers on LinkedIn, have likely seen my social media posts about these activities. But, what exactly happens on these trips, and why does it matter?

As you know, I wrote a book called History, Disrupted: How Social Media & the World Wide Web Have Changed the Past. The book examines how and why certain information about history becomes visible and influential online. Even before the book was published, this was an interest of mine for many years. I wrote articles in CNN, TIME and other outlets about how the web and social media were changing what we knew about history right before our eyes—and the consequences that might have for democracy, education, media literacy and international relations.

My first engagement with DOS occurred in 2017, five years before History, Disrupted was even published. At the time, I was the founding director of the Lepage Center for History in the Public Interest when I received an email with the subject line, “Speaking opportunity in Vilnius, Lithuania” from someone identifying as an Assistant Public Affairs Officer at the U.S. Embassy. I thought it was a scam. But the email signature seemed authentic, so I replied to learn more.

Lithuania was confronting a surge of Kremlin-sponsored propaganda on social media and the Web. Some of the propaganda was “fake news”; a fake story, for example, alleging that U.S. troops in Latvia were poisoned by mustard gas (completely false, never happened). A lot of it, though, was “fake history;” the weaponization of Soviet-era nostalgia in the hopes of swaying the population away from “the West” (i.e., Europe and the U.S.) and towards Moscow. The American embassy had been in touch with Lithuanian nonprofits, universities and government officials as they monitored this growing trend, and they were looking for a speaker who could come to Lithuania for a week and talk with these stakeholders about media literacy, historical literacy, and how to decipher honest history from propaganda online.

So, I traveled to Lithuania the first week of May 2017 to address these subjects. The embassy arranged for me to speak to students at three universities (Vilnius University, Vytautas Magnus University and Mykolas Romeris University); deliver a lecture to Lithuanian history teachers and educators; meet with the staff of the Vilna Gaon Museum of Jewish History; and be interviewed by the Lithuanian magazine IQ. The goal was to advance what I and the State Department both believed to be true, namely that honest and accurate history were essential to democracy—and that the weaponization of nostalgia online served only to advance the goals of authoritarians.

The trip received positive feedback and paved the way for my next trip to France in 2019. At the time, France was in the midst of the “Yellow Vest” movement. The movement was fueled by social media, particularly Facebook, and there was a wave of disinformation being generated by opportunistic actors, including Russia.

The State Department, in collaboration with the German Marshall Fund, asked me to speak about similar topics in France as I had in Lithuania—fake news, fake history, media literacy and historical literacy—with similar audiences, i.e., universities, government officials, young professionals and journalists. The highlight was a public event held inside the stunning Hôtel de Talleyrand in Paris, a beautiful historic mansion that formerly served as the American headquarters for the Marshall Plan.

The Covid-19 pandemic brought international travel to a halt, and I did not think my engagements with the State Department would continue. But two things happened in 2022: History, Disrupted was published in January and Russia launched its full-scale of invasion of Ukraine in February.

The seeds for the Russian military invasion were planted years ago, when Putin declared the dissolution of the U.S.S.R. to be a “geopolitical disaster” and when he penned a lengthy essay claiming that Ukrainians and Russians are “one people” who must be united in a single homeland.

For four years, Putin had a pro-Russian ally as the Ukrainian president, Viktor Yanukovych. But after Yanukovych publicly turned his back on the European Union and embraced Russia more openly, Ukrainians ousted him in a revolution in 2014. In response, Putin’s forces stealthily invaded Crimea, dismissed the Crimean government, installed a Putin loyalist, and held a referendum that claimed to overwhelmingly favor leaving Ukraine and becoming part of Russia. Crimea has remained under Russian occupation ever since; ten years later, Putin is in the midst of a full-scale military attack on Ukraine with the goal of annexing the entire country.

Despite what some Americans may hear, what happens in Ukraine matters greatly to the United States. There are many reasons, but principally:

The U.S.-led world order established in the 20th century after two world wars rests on the idea that the sovereign borders of a country must be respected. Putin has flagrantly violated that rule, illegally annexing part of Ukraine and trying to destroy the rest of it;

If Putin succeeds, it could embolden others to do the same. Imagine if China decided to unilaterally change borders in the Pacific through an overt or covert invasion. Or if India attempted to unilaterally change borders on the Asian subcontinent. Or Brazil in South America. Each of these countries have chosen to officially remain “neutral” towards Russia’s invasion, effectively condoning Putin’s actions and possibly studying his playbook to achieve their own ambitions;

Putin, himself, will repeat this playbook in other countries if he succeeds in Ukraine. Georgia and Estonia are two countries he has already spoken about “reclaiming” in the name of the former Russian empire;

This puts tens-of-millions of people who currently live in democracies at risk of being under the rule of an autocrat with no regard for human rights—something we promised after World War II would not happen again;

Finally, the European Union, I would argue, is America’s most reliable and steadfast ally, critical to our economic and military interests, as well as the NATO alliance. Our collaboration with Europe helps ensure hundreds-of-millions of people can live in democratic societies. If Europe falls under Russian influence, we lose our most important partner in propping up democracy, human rights and freedom itself.

Again, these are my views. I recognize these notions may be opaque to everyday Americans struggling to pay their bills or find a job. This is why we employ diplomats around the world, to uphold these values on the global stage.

In the wake of Putin’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, this work has become even more urgent.

As fierce as the Russia-Ukraine war has been on the battlefield, it has been equally fierce online in the domain of history. Putin’s justifications for war are rooted in distorted historical arguments that are amplified 24-hours per day, 7 days per week, 52 weeks per year across Russian media channels, as well as media and social media aligned with, or sympathetic to, the Kremlin.

The narratives are complex, and cannot be done justice here. In brief, they situate Ukraine as central to defining what Russia is, rooted in a historical mythology around Kyivan Rus’, the first East Slavic state that existed centuries ago. The argument is that Kyivan Rus’ (Kyiv is the current-day capital of Ukraine) has always been integral to Russian history, and that today’s Ukrainians are really Russians. Russia, in this argument, is reclaiming territory that has always been “Russian,” liberating it from nefarious foreigners such as the E.U., NATO and the U.S.

While honest people can debate the historical origins of the Russia-Ukraine relationship, the distorted “history” that Putin uses to justify his invasion overlooks long histories of Ukrainians fighting for their own independence, not to mention the diversity within Ukraine that includes people of Hungarian, Romanian, Tatar, Bulgarian, and Armenian descent—clearly not all ethnically Russian—as well as the diversity of languages, cultures and religions that comprise Ukrainian heritage. The “history” the Kremlin espouses resembles propaganda and disinformation more than it does serious scholarship.

Understanding how history operates online and in the media, then, has enormous consequences for our geopolitical moment. Since I, literally, wrote the book on how history operates online, my passions align well with the current priorities of the State Department to counter disinformation and promote media literacy, historical literacy, critical inquiry, and democracy rooted in honest and accurate interpretations of the past. If one looks at the list of countries I’ve traveled to, they either border Russia or Ukraine, or are seeing major Russian influence campaigns within their borders.

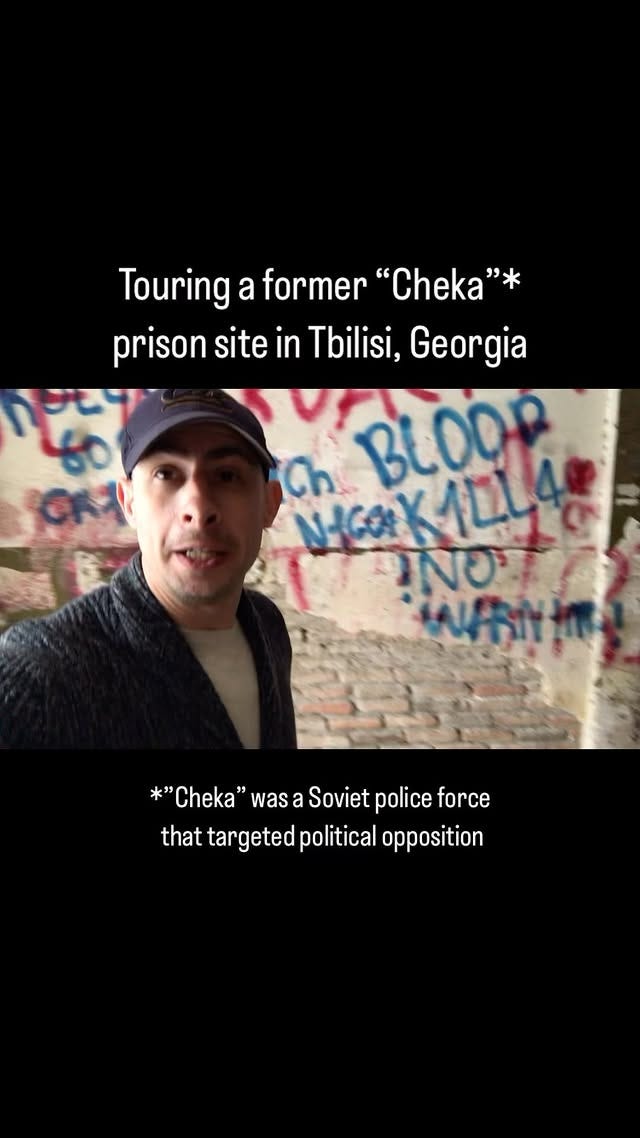

Take Georgia, for example. In May 2023, I spent three days in Georgia working with an organization called SovLab. SovLab is a civil society organization that studies the Soviet Union’s history in Georgia, including the repression of dissidents and torture of Georgian civilians who spoke out against the regime. SovLab brought me to a former “Cheka” prison site wherein Soviet police captured and tortured political opponents.

Today’s propaganda efforts by Russia in Georgia paint a very different historical picture: that of Stalin (who was Georgian by birth) as a hero, mixed with nostalgia for a benevolent Soviet empire. This relentless propaganda campaign has, as it did in Ukraine, laid the groundwork for political action. Georgian Dream, a political party sympathetic to Putin, has recently seized control of Georgia through a disputed election, publicly turned its back on the European Union, and has deployed police to beat and maim protestors—a playbook eerily similar to Ukraine. Meanwhile, Russian forces in the north of Georgia have been laying the groundwork for annexing part of the country and changing its borders.

Romania is another example. I spent five days in Romania in October 2024, first as part of the American delegation to the international Conference on Holocaust Distortion and Education, and then as a speaker with the U.S. embassy. The embassy arranged for me to meet with university students, think tanks, journalists and the Romanian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. I was also interviewed on a Romanian podcast. (Side note: the podcast host had read my book, and when the embassy informed him I was coming, he was incredibly excited. That was very heartwarming).

Today, Romania is a democracy, but it has a long history of dictatorship, complicity in the Holocaust, and a secret police force, the Securitate, that imposed terror and repression on political opponents for decades. According to experts I spoke with, Romania remains susceptible to autocratic influence. “Romanians think it can’t happen here, but it could,” I was told by one think tank. “We think we are one step ahead of the Russians, but we underestimate how good they are at this.” A few weeks later, the pro-Russian candidate Calin Georgescu won the first round of Romania’s presidential election, leveraging anti-U.S. and anti-E.U. narratives while campaigning on TikTok. The next round of elections, scheduled for December 8, was recently postponed due to mounting evidence of Russian interference.

Historical narratives circulating on social media have the potential to change the course of nations and entire regions. This is not only true of Russia; in my travels, I have seen how this affects nearly every country:

In Kosovo, where I participated in the first-ever Balkan Disinformation Summit in February 2024, historical debates online center on a long-standing feud with Serbia over Kosovo’s independence. Not surprisingly, Kosovo, which wants independence, supports Ukraine; Serbia, which wants to annex Kosovo, supports Russia;

In Bulgaria and North Macedonia, where I traveled in May 2023, the two countries have been fighting over history for years, including who is to blame for the deportation of 11,000 Jews from Thrace to Treblinka during the Holocaust. Thrace was in Macedonia at the time, but was occupied by Bulgaria. Both blame the other for the atrocity;

In Hungary, where I spoke in June 2023, grievances over lost territory from Hungary’s past are part of the fuel for Viktor Orban’s nostalgic authoritarianism that has captured state and civil society institutions across the country;

In Belgium, where I’ve worked with our embassy twice, Flemish nationalists are exploiting historical narratives and imagery to gain political power, advocating for secession from Belgium and creation of an independent state of Flanders.

How history circulates online matters greatly to world affairs today.

What happens inside the borders, and in the elections, of other sovereign nations are their decisions, not ours. I do not travel to other countries to try and dictate events—nor could I, if I wanted to.

What can American public diplomacy realistically do, then? We can lend our expertise, advice and support to our partners and friends who are fighting for democracy and freedom.

In each country I’ve visited, our embassies have done an incredible job of connecting me to like-minded people and organizations who share the same values:

That honest and accurate history should be independent of state influence;

That independent media should be able to report honestly about politics and society;

That critical thinking that questions nostalgic and simplistic narratives is crucial to a democracy; and,

That media and historical literacy help citizens understand what they are seeing on social media and the Web.

Upholding these values creates a healthier, better educated, and more democratic society. It also helps guarantee individual freedoms and keeps political power from being abused.

My diplomatic efforts over the past seven years, then, have comprised countless meetings and conversations where we share expertise, forge relationships, and find ways to collaborate in order to advance these objectives. American embassies also make grants available to organizations who do this work; bring individuals to the United States to learn how we operate here; and encourage students and citizens to understand the importance of historical and journalistic integrity. That’s some of what public diplomacy entails—and it is well-worth the investment, in my humble opinion.

Throughout this work, it has become evident to me how much of what happens in Europe does not get reported in the American press. Unless there is an election or political violence, the dynamics in Belgium, Bulgaria, Hungary, North Macedonia, Kosovo, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, and Romania rarely makes the news. One has to search hard on the major media sites to find substantive information on these complex places.

🎙️ This gives me an idea: a series of podcast conversations with the individuals I have met in my diplomatic work who are on the front lines of fighting for democracy, media literacy and honest and accurate history and journalism.

These are amazing people, often times standing up for principles in the face of long odds, powerful opposition, and without much support. They are individuals in places such as Hungary, North Macedonia, Bulgaria, Germany and Georgia that most Americans never hear from, and likely never will.

🎁 This holiday season, I’m asking for your help in making this podcast a reality.

A good podcast requires resources for editing, marketing and production. If you believe that hearing the stories of these amazing people would be worthwhile, please consider helping to make it possible. You can:

Become a paid subscriber to this newsletter;

Donate via cryptocurrency: 0x97612266209D94dFcea09Bd9F02ED9cE336FBB58

If you’re a podcast producer, and would like to donate your talent in-kind, that would be wonderful, too. Any and all support will be put towards the creation of this series, precise launch date TBD.

Will my work with the State Department continue? I hope so. It may depend upon the incoming administration’s priorities. Whatever those priorities, I hope the powers-that-be recognize the important role public diplomacy plays in trying to make a better world.

The State Department does not always get it right; the department has made mistakes over the years, some with dire consequences. But for my part, I’ve found everyone I’ve worked with at DOS to be smart, engaged and with their hearts in the right places.

Citizen diplomacy and public diplomacy are part of how I try to keep the fragile soil of democracy from eroding beneath our feet. Mine is a small contribution; there are others doing much more. But, to quote Pink Floyd, I would rather have a walk-on part in the war than a lead role in a cage.

Freedom, after all, is worth fighting for.

Have a good week,

-JS

Or contribute via cryptocurrency: 0x97612266209D94dFcea09Bd9F02ED9cE336FBB58