The TikTok ban in historical perspective

America has a long history of debates over speech

Many Americans consider Abraham Lincoln to be our greatest President. In part, this is because he abolished slavery in the United States through his Emancipation Proclamation; in part it is because he steered the U.S. through a bloody and divisive Civil War; and in part it is because of his political skill in doing both.

Yet, there were aspects of Lincoln’s presidency that made Americans highly uneasy, both during his lifetime and afterwards. Lincoln did whatever he thought was necessary to win the Civil War, including instituting a mandatory draft, dramatically raising taxes and imprisoning Confederate sympathizers without trial in a floating prison off the coast of Manhattan called Fort Lafayette. By the middle of the war, he had notorious anti-war speakers and peace activists deported. Most egregiously, perhaps, he shut down newspapers that criticized his administration. He sent the military to their headquarters, arrested their editors, and threw them in prison. He squashed their ability to send news through the mail, suppressing their circulations. When Americans protested these infringements on their individual liberties and Freedom of Speech, Lincoln responded coldly that they were necessary in the name of national security.

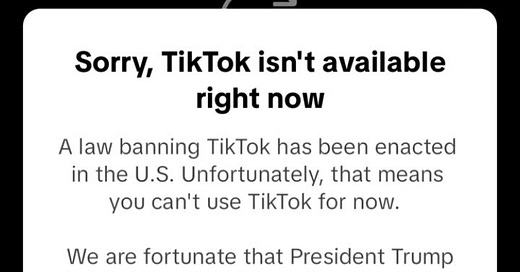

I could not help but think about President Lincoln this weekend as TikTok went dark in the United States. The analogies are imprecise, of course; the algorithmic power of TikTok in the hands of 170 million Americans is something that newspaper editors of the 1860s could have only dreamed about. Imperfect as the analogy is, there is something familiar about an era’s most powerful communication platform being shut down by senior levels of government under the guise of national security. The text of the First Amendment of the Bill of Rights, one of the foundational tent-poles of the American experiment, states clearly that “Congress shall make no law abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press.” How, then, can a ban of an entire communication platform, albeit a controversial one, be permissible in America—then and now?

I will disappoint you upfront by saying that I will not offer a concrete opinion on whether a forced sale of TikTok is “right” or “wrong.” I’ve been asked this question many times in the past two years, sometimes in the presence of lawmakers with power to make such decisions. Instead, I will offer what I have offered repeatedly in these instances: a line of questioning that you can use to think through the issue on your own terms. Perhaps, by applying your own reason and intellect, you can make up your own mind. History does not offer easy answers, only difficult questions. To paraphrase the Austrian poet Rainer Maria Rilke, if we embrace these questions, perhaps gradually, we will find our way into the answers.

The circumstances surrounding Lincoln’s suppression of speech during the Civil War were complex. It bears remembering how influential newspapers were in 1860s America. There were no computers, radios, television, email, mobile phones or social media platforms. The U.S. had more than 2,500 newspapers and these newspapers (and magazines) were the principal ways that Americans learned about what was happening in the world and the actions of their government.

The newspapers were not neutral conveyors of news; they were very much aligned with political parties. For example, the mayor of New York at the time was a man named Fernando Wood, a Democrat. His brother, Benjamin Wood, ran the New York Daily News as a Democratic mouthpiece. Benjamin Wood made no secret about his politics; readers knew where the Daily News stood on the issues. The same was true of the New York World, Brooklyn Daily Eagle, and Weekly Day Book. These papers were unabashed in their support for Democratic politics, both in their editorial pages and in how they reported the news.

The Democratic Party of the 1860s was not the same party that we know today (Lincoln was a Republican, a relatively-new political party founded, in part, to oppose the expansion of slavery). Descended from the Democratic-Republicans of prior decades, the Democratic party had a tradition of representing the interests of wealthy aristocratic Southerners. Combined with a raging populism inherited from President Andrew Jackson, by the time of the Civil War the Democratic press were aggressive defenders of slavery, argued repeatedly for the rights of states to decide what happened within their borders, and insisted on an immutable inequality among races that under no circumstances would permit Whites and Blacks to be equals.

These ideas existed in Democratic newspapers prior to the Civil War; once the fighting between the North and South began, they became even more vicious. As the war turned deadly and gruesome, the Democratic papers became more critical of Lincoln. They demanded an end to hostilities and a return to “The Constitution as it is, the Union as it was” – in other words, a United States where slavery could still exist and expand.

In fall 1862, Lincoln declared his intentions to emancipate all enslaved persons, a necessary action to provide moral footing for the war and rally enlistment among Black soldiers for badly-needed reinforcements. The Democratic press became even more infuriated when the Emancipation Proclamation became official on January 1, 1863. Not only was this a massive overreach by a despotic and power-hungry Executive Branch, they argued, it revealed a conspiracy that had been in the planning all along: that the blood of White Americans was to be spilled for the benefit of African Americans. Among White supremacists within the Democratic press, this unleashed a torrent of hateful rhetoric in newspapers, pamphlets and speeches that would make our 21st century ears recoil in horror.

As odious as this speech was, should it have been protected under the First Amendment? Democratic editors believed so, and for the most part it was.

However, at key moments during the war Lincoln suspended the free speech and free press rights of American citizens. Early in the war, Lincoln suspended the writ of habeas corpus along the East Coast in the name of “public safety.” The State of Maryland, in particular, was a hotbed of Confederate sympathy and anti-war activity, some of it violent. Lincoln had agitators arrested and denied their “writ” (a.k.a. their right) to appear before a judge and contest why they were being detained. He even ordered the arrest of members of the Maryland state legislature. Lincoln, and later Congress, would suspend such rights several times during the Civil War, each time arguing that since the President is charged with the preservation of public safety, during periods of rebellion or heightened danger the Constitution permitted such warrantless arrests.

Lincoln did not stop there. One of Lincoln’s fiercest critics was Clement L. Vallandigham, an Ohio politician who railed against Lincoln in a series of highly-publicized anti-war, pro-Confederacy speeches. In 1863, Lincoln had him arrested, tried by military commission, and deported. In 1864, Lincoln ordered the military to seize the New York offices of the Democratic Journal of Commerce and New York World newspapers and to imprison their editors and publishers after they published a fabricated document “meant to give aid and comfort to the enemies of the United States.” That was after Lincoln had suppressed or shut down newspapers in Maryland, Missouri, and Kentucky. In total, approximately 300 newspapers were shuttered during the war, arguably the greatest violation of the first amendment in American history.

The U.S. Civil War was not the only time that government suppressed the speech of American citizens.

During World War I, “alien enemies” within the U.S.—principally German Americans but extended to others—were denied their rights to criticize the U.S. government, as were various elements of the American labor and socialist movements, hundreds of whom were arrested for “anti-war activities.”

On the eve of World War II, students who were Jehovah’s Witnesses refused to say the Pledge of Allegiance in class. The school expelled the students and the Supreme Court ruled against their exercise of freedom of speech and religion, citing the necessities of “national cohesion” and “national security.” The ruling was overturned a few years later. Around the same time, Japanese Americans across the U.S. were interned under Executive Order 9066, a gross violation of their fundamental rights.

And during the Civil Rights movement, the FBI routinely surveilled Civil Rights leaders and organizations in an attempt to “disrupt,” “discredit” and “neutralize” the speech and free expression of activists. The justification used was to head off the threat of communism and other radical elements in the name of national unity and national security.

Each of these moments in American history were so complex as to warrant thousands of scholarly books and articles. Analogies among them are fraught with pitfalls—which is why as historically literate information consumers, we know that simple historical analogies do not provide simple, straightforward answers.

A better approach might be to ask ourselves what recurring themes have been used by government officials to bypass the protections enshrined in the U.S. Constitution?

One commonality has been the perceived threat posed by an enemy within our borders. To root out the “enemy within” often becomes the justification for government suppression of rights.

During the Civil War, the enemy within were pro-Southern voices agitating in the Northern press. During World War I, they were German Americans and “Bolshevik” (socialist) sympathizers. During World War II, it was Japanese Americans. During the Cold War, it was Communists. In every age, there is always an enemy inside the gates whose apprehension is so critical that, it is argued, civil liberties must be disregarded.

Since our government works for us, though, we have a right—an obligation, in fact—to ask questions of our government officials. At what point do justified concerns bleed into unjustified paranoia? Did any one individual newspaper editor during the Civil War pose an existential threat to the Union? Did a handful of anti-war socialists during World War I truly threaten the American war effort in Europe? Did Japanese Americans during World War II pose any real risk to American security? Was the Civil Rights movement any plausible threat to “national unity”?

In the moments, some government officials argued “yes.” With hindsight, however, the historical argument has often been revised to “no.” Even in the case of Lincoln and the Civil War, as racist as some of the Democratic newspapers were, ultimately it was the Union victories on the battlefield, a belief in the sanctity of a United States, and the moral necessity of eradicating slavery that proved decisive. Most of the historical scholarship suggests that imprisoning certain newspapers editors had little-to-no effect on the outcome of the war.

Another commonality has been that when America is at war, the fight never stays confined to the battlefield. It spreads to all corners of society, with some ideologies, nationalities and political affinities deemed too dangerous to be allowed to persist. The rationale is usually couched in the language of “national security,” “public safety” or “national unity.” But, of course, as historically literate citizens, we know that these are highly contested terms that change their meanings over time. We also know that a national unity in favor of slavery, for example, is not a unity we can morally accept. Eradicating that unity and replacing it with a consensus around equality and human rights is an act of patriotism worth disrupting the status quo for. And, we know that part of what allows America to win ideological and moral battles—in addition to physical ones—are the ideals expressed in our founding documents.

Speaking to those ideals, in overturning the Jehovah’s Witness decision on the Pledge of Allegiance, Justice Robert Jackson of the Supreme Court wrote eloquently in 1943 that we should never allow the fear of dissenting opinions to restrict the diversity that makes us free:

“We apply the limitations of the Constitution with no fear that freedom to be intellectually and spiritually diverse or even contrary will disintegrate the social organization. … [F]reedom to differ is not limited to things that do not matter much. That would be a mere shadow of freedom. The test of its substance is the right to differ as to things that touch the heart of the existing order.”

Which brings us to the question of TikTok in the United States. TikTok is owned by Bytedance, a multi-billion-dollar private equity company headquartered in China. Launched in 2018, today TikTok has an estimated 170 million users in the United States and more than 1 billion users around the world.

At the heart of the debates around TikTok in the U.S. are three central questions:

As a mega-corporation based in China, is the data that TikTok collects about Americans available to the Chinese Communist Party to use however it wishes?

As a sophisticated artificial intelligence program on the mobile devices of 170 million Americans, can the app be used for surveillance, propaganda and subversion of American interests?

As part of the broader geopolitical competition with China, can the U.S. abide one of the world’s most powerful algorithms operating on its soil under the ownership of a “foreign adversary”?

The most recent U.S. Congress and President Biden, who signed the law, said “yes” to the first two questions and “no” to the third. As such, TikTok now faces a decision whether to sell the app to an American owner or shut down in the U.S. – and President Trump must decide whether to enforce the law, try repeal it, or negotiate a different solution.

As part of the debates around TikTok, Americans might have been surprised to learn that some of their elected officials and business leaders believe the U.S. is currently at war with China… even though no such war has officially been declared. That “war” is for global supremacy; China is the only country that rivals the U.S. in size of military, size of economy, technological capabilities and global influence. As the chief “foreign adversary” to the U.S., China has been found to be stealing our trade secrets, conducting surveillance and espionage on our soil (remember the mysterious balloon over the American West), undermining American interests abroad, and spewing anti-American disinformation and propaganda. As in prior eras, the perceived threat is the enemy inside the walls—or in this case, the enemy inside the palms of our hands.

Lincoln had argued that periods of heightened danger allowed a President to suspend individual liberties to quell such enemies. A war against an armed rebellion was a clear moment of “heightened danger”—but what about a global competition against an emerging superpower? Does that count as a period of “heightened danger”? Who decides: Congress? The President? The American people? When elected officials seek to make laws that undermine certain rights and advance their pre-conceived objectives, are they at liberty to declare any perceived threat a “heightened danger”?

In prior eras, the suppression of speech often affected racial and ethnic minorities (Japanese Americans, German Americans, Black Americans). In the case of TikTok, it represents 170 million Americans of all racial and ethnic backgrounds and socio-economic levels. Granted, the content of the speech that Americans perform on TikTok is not being regulated; it is the platform itself that Congress and The White House have deemed a threat. Americans are free to continue making short-form dance videos—they will just have to do it on an American-owned social media site.

It is worth asking ourselves whether the issues around TikTok would have been raised were the app to be owned by a company in any other country. Meta, for example, aggressively collects the data of Americans each day and uses it for a myriad of opaque purposes. But they are an American company. Meta, in fact, has been an aggressive driver behind-the-scenes in lobbying for a TikTok divestiture, as their apps (Facebook, Instagram, Threads) stand to benefit if TikTok disappears.

The technology of TikTok is, indeed, highly problematic; my History Communication Institute issued a report in 2022 articulating numerous concerns with TikTok’s addictive algorithm, unethical business practices, and massive AI facial recognition technology. If TikTok were to be regulated as a dangerous product under the premise of consumer protection, that would be one thing. But it is being regulated under the premise of national security and the possibility that it is being used as a propaganda tool by the Chinese Communist Party. Those are powerful claims that should be critically examined by lawmakers and the voting public.

Ultimately, our political leaders work for us. As such, we should be asking them hard questions about this law and receiving clear and honest answers. Are there certain technologies that are too dangerous to be widely used? Are those technologies only too dangerous when they are operated by certain nations, and not by others? Are we legislating against another perceived “enemy from within” – and, if so, what influence does such an enemy truly have relative to other factors? What precedent is being set by forcing the divestiture of one particular communication platform among many? Can any company or platform determined to be a threat to “national unity” or “national security” be subject to a similar fate in the future—perhaps one that disagrees with a sitting President or advocates for radical policies that deviate from the status quo?

Lincoln was assassinated in 1865, so he never had the chance later in life to reflect on his decisions to suppress speech and civil liberties. It is not worth speculating how he would have felt; such a counterfactual is impossible to surmise (though ChatGPT could probably invent an answer).

Plenty of historians and biographers have examined Lincoln’s actions, though, acknowledging that they played little, if any role, in determining the result of the Civil War. The imprisonment of dissenting socialists during World War I likely had little-to-no effect on that war’s outcome, either. Interning Japanese Americas did not help the effort in World War II; in fact, it probably hurt it. And the Civil Rights movement persevered even despite all the attempts to stifle it.

History often reveals that the suppression of speech rarely, if ever, leads to the eradication of ideas. Ideas evolve and migrate, and if one platform shuts down another takes its place. Suppression can certainly be effective in the short-term. But in the longer struggles, the ones that really matter, freedom usually offers the decisive blow.

Have a good week,

-JS

An awful lot to unpack here. I'll have to think long and hard about this, as everyone should. Thanks.

Great piece, Jason. Never knew this about Lincoln. Good defense of free speech on your part.