Why are so many American men dying?

Diseases of despair are pushing up the death rates for males

History Club remains on break while I work on my book manuscript. Stay tuned for an updated schedule.

Joel Pomerantz died recently. Unless you were a musician in the Washington, D.C., area you never met Joel. He was a staple in the D.C. music scene, best known for supporting local artists at his venue Electric Maid. He booked scores of acts large and small, and traveled across the region attending the concerts of bands that most people never heard of. Last month he suffered a stroke, and passed away a few weeks later. He was 64 years old.

Joel died less than two months after my friend Edgar. Years ago, Edgar had been the drummer in my rock band. He was 57. Edgar was the second of my former bandmates to pass; my keyboardist, Josh, passed away at the age of 40. That was a few years after Kevin, a friend of mine in New York, died suddenly in his mid-30s. After Kevin there was my co-worker Patrick who died of a heart attack at age 36; my cousin Neil; my other cousin Bobby; a former scholar at the Library of Congress Lamin Sanneh; a former webinar co-presenter of mine Jon Tennant; another former co-worker of mine from the music industry, Joe Ramaikas; historian Lonn Taylor (who we dedicated a special History Club episode to in April); and historian Barry Lewis, in whose memory we dedicated the recent History Club, Live from New York.

People die, of course. As we age, it happens to more people we know. In my life, it has been overwhelmingly men and frequently men of younger age. This got me wondering: (1) Is this a coincidence or indicative of a broader phenomenon, and, if so, (2) Why are so many men dying in America?

According to the U.S. Center for Disease Control (CDC) the life expectancy for American males is consistently lower than for females, and more men die each year than women. In 2018, the life expectancy difference was 5 years, the same as in 2017. American men can expect live until the age of 76, while women can expect to live to 81. For American Indians and Alaska Natives males, the life expectancy is lower.

The leading causes of death for American men are heart disease, cancer, unintentional injuries, chronic lower respiratory diseases, stroke, diabetes, Alzheimer’s, suicide, influenza and pneumonia, and chronic liver disease. These are mostly similar to women save three notable exceptions. First, unintentional injuries (a.k.a. violence and accidents) are almost doubly fatal for men. Second, suicide is among the top ten for men but not for women. Third, chronic liver disease (i.e., alcoholism), is among the top ten for men but not for women. Violence, suicide and alcohol account for 12 percent of American male fatalities.

Covid-19 has also been more lethal for men than for women. Though the infection rates are roughly equivalent, researchers publishing in the journal Lancet found Covid-19 to be more fatal for males, a difference that was statistically significant. The researchers suggest the effects are cultural, not genetic. Contributing factors include drug use, alcohol use, occupational hazards, medications, and co-morbidities such as obesity, diabetes, kidney disease and asthma.

All of this portends that while there may be natural difference between the sexes, the rising mortality of American males has cultural and historical roots. Several scholars have attempted to diagnose what they are. In 2018, Andrew Yarrow published his book Man Out: Men on the Sidelines of American Life. Yarrow estimates that 20 million men have fallen out of the labor force since the Great Recession of 2008-09. These non-working men struggle to obtain health insurance, lack stable income, are more likely to be asset-poor and have little-to-no savings. They are also less likely to be married, or have a partner to help with income, savings, and insurance. All of this leads to negative health outcomes, including drug addiction, alcoholism and suicide.

Additional scholarship has correlated the joblessness among working-age men to increases in drug overdoses, suicides, and alcohol-related liver mortality—particularly those without a college degree. Even as mortality from cancer and heart disease have improved, so-called “deaths of despair” continue to climb. According to one study, the rate of deaths of despair recently doubled in the United States in both rural areas and urban areas, particularly among whites. The determining factor was not gender but education. Both men and women with less than a four-year college degree saw their mortality rates rise between 1998 and 2015.

In Appalachia, a region of the country that has been a subject of much scholarly and popular writing, males have experienced a higher burden of mortality due to diseases of despair. The burden of diseases of despair was more than double that of females, with a mortality rate of 121 per 100,000 (compared to 88 nationally). Men in Appalachia died at double the rate of women from drug and alcohol use, and at triple the rate from suicides. The opioid crisis has exacerbated the situation. In 2018, overdose mortality was significantly higher in Appalachia than the rest of the country, particularly in economically distressed counties and metro areas.

For African American males in cities, the statistics are equally grim. A study in 2001 found that fewer than half of the 16-year-old males in poor urban areas could expect to live through middle age. Fewer than 10 percent were expected to live to age 85. Men make up more than 80 percent of gun violence perpetrators and victims, and out of nearly 40,000 firearm deaths in 2017, men made up 86 percent of them. In American prisons, men are dying from cancer, heart disease, AIDS and suicide, particularly Hispanic males. One study found that Hispanic inmates commit suicide at a rate about 23 percent higher than Black inmates.

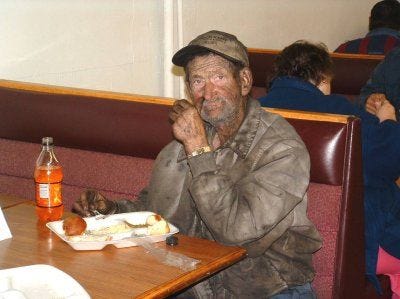

More studies and more statistics could be cited. But from this sample, a picture begins to emerge. In places of poverty—whether it is in Appalachia, inner cities, on tribal lands, or in prisons—American men are dying younger and more often. One the one hand are chronic health conditions brought on by poor living conditions, poor sanitation, poor nutrition, lack of health insurance, lack of access to medical facilities, lack of financial resources, and polluted environments. On the other hand are diseases of despair, principally violence, drug abuse, alcoholism, and suicide. Lingering above it all is a labor market undergoing seismic changes. Low-paying service work has replaced well-paying middle and upper-class industrial jobs. Wages are stagnant. The skills for white collar work change rapidly due to technology. And the costs of higher education have increased exponentially. For American men who have fallen behind or fallen out, catching up has become nearly impossible. Each factor compounds the other.

Many inequities persist in our society, of course. Men who do work earn more than their women counterparts. At least one million fathers are behind bars, overwhelmingly people of color. Black women continue to die in childbirth at far greater rates than white women. We have many issues to solve, many economic and racial gaps to close. Though some make the headlines more than others, all of them require our commitment. The loss of so many of our fathers, brothers, sons and friends is one of them.

Have a good week.

History Club meets Thursdays at 10 pm ET exclusively on Clubhouse. Want to participate? Suggest a topic for a future conversation.

Haven’t supported the History Club? Please consider it. Your support allows me to publish posts like this.