“When I came back from the war, I, like so many others, hated politics and politicians, who it seemed to me, had betrayed the hopes of the fighting men… Return the country to [those] who had bartered every ideal? No. Better [to] deny everything, destroy everything in order to build everything up again from the bottom.”

-Italo Balbo, military official, Italian Fascist Party

At the end of World War I, Italy sat at a crossroads. The war had killed 650,000 Italian soldiers. Italian politics were fractious and dysfunctional. Regional rivalries had long beset the Italian national project—the south agrarian and largely impoverished, the north industrial and trending towards socialism—and the government in Rome seemed incapable of unifying the country. Unemployment surged, and despite being on the winning side, grievances persisted against the League of Nations for unfair treatment during peace negotiations. A deep cynicism and frustration simmered throughout the country, largely directed at the establishment classes.

Into that cynicism stepped Benito Mussolini. A newspaper editor and columnist of limited name recognition—and who only briefly served in the war—Mussolini weaponized Italy’s economic and political frustrations to fuel his own ambitions. In 1919, he and a small group formed what they called the Fasci di Combattimento, or the “Fighting Fasces,” the first official fascist party in Europe. They promised to cure Italy of its “national cowardice,” and to replace its weakness with strength. They promised to stamp out the socialists and Marxists, and restore law and order. They promised to return Italy to its past glories.

Past glory was endemic to the very foundation of the movement. The term “fasces” came from Ancient Rome, a golden age of the Italian past that was viewed as a model and an inspiration. The fasces were bundles of wooden rods, tied together with leather straps and an axe protruding. They were carried by attendants waiting on Roman high officials, and were meant as a symbolic show of force. They could be used at any moment for corporal punishment, and were intended to instill fear and respect for authority into those who viewed them.

For the Italian fascists of the 1920s, the allusion to Ancient Rome was meant to reinforce the strong leadership that Mussolini and his new party would bring. That strength would be buttressed by violence, including Black-shirted militias inspired by the clothes of Roman laborers. The fascist militias would soon attack their perceived enemies and stage a coup that subsumed the previous Italian government, holding power for twenty years before their collapse in World War II. Millions of Italians supported or enabled them, as did politicians, journalists and citizens in other countries. (Several American newspapers and politicians praised Mussolini during the 1920s and 1930s.) Fascist movements soon emerged throughout Europe and spread across the world, many still in existence today and new ones forming.

What has made fascism so appealing—and why does it remain so attractive one hundred years later? Allow me to use this week’s newsletter to offer some ideas.

“Fascism” and “fascist” are words that are commonly used but not always precisely defined.

Fascism is, at heart, an ideology—a word that is also difficult to define. Generally speaking, an “ideology” is a set of integrated ideas and beliefs held by a specific political group. Fascism, then, is best defined not by particular people (Mussolini, Hitler, etc.) but rather by a set of common beliefs held by a cluster of political movements. Fascists across multiple countries and time periods tend to adhere to a similar set of ideas, and use a similar suite of tactics to put those ideas into practice. Those beliefs include a dictatorial leader at the helm of government; a mandate for fierce loyalty to the party and the nation; a disdain for the structures of democratic governance; and the forcible suppression of dissent and opposition. By virtue of holding such beliefs and executing them across society, a political group comes to embody a fascist ideology.

The notions of an all-powerful leader and compulsory loyalty did not originate with fascism. In the case of Mussolini and the Italian Fascist Party, a range of past ideas—including from the Roman Empire, the French Revolution and Napoleon—were incorporated into their belief system. What distinguished 20th century fascism from its predecessors was the rooting of those beliefs inside the nation-state, intertwined with virulent strands of nationalism. Ancient Rome was an empire comprised of subjects; Italy was a country comprised of individuals bound together by an Italian national identity. That nationality was imagined as having a common past, a common language and a common set of beliefs (e.g., a shared religion of Christianity) that distinguished them from those who did not share those traits. The loyalty that fascism demanded was not solely to the leader and the party, but also to the nation-state and its preferred characteristics.

The most well-known example of 20th century fascism, Nazi Germany, makes these abstruse concepts more concrete. Like their counterparts in Italy, the Nazi Party used force and coercion to assume and hold power, and violence and intimidation to suppress dissent. The party demanded loyalty to the Fuhrer, as well as loyalty to the idea of the German Nation (the “Volk”). Disloyalty to the nation was a form of treachery, and the purity and greatness of the nation became the party’s sacrosanct goal. This warped belief in national purity and racial hierarchy ultimately led to genocide against those deemed inferior or alien, including Jews, Roma, homosexuals and the intellectually and physically disabled.

The violence of fascist movements is what most of the general public remembers. But 20th century fascism was marked by many other beliefs and strategies that were far more mundane. It was these strategies that earned the movement popularity in Italy and Germany, as well as Greece, Hungary, Romania, Spain, Bulgaria and Yugoslavia, as well as around the world. These included:

Disdain for international institutions

Both Mussolini and Hitler decried the influence and betrayal of international institutions on their nations. They argued that international organizations—and the elites who supported them—had put shackles on the nation’s greatness and prevented them from achieving territorial and economic expansion. Both Mussolini and Hitler pulled their countries out of the League of Nations under the pretense that they were treated “unfairly” during the peace negotiations after World War I, and they made internationalism a scapegoat for complex political and economic problems. In fascist Romania, the disdain for international institutions was coupled with antisemitism to brand Jews as the “ultimate evil,” representative of a foreign corruption “poisoning” the Romanian nation.

Lamenting national weakness and promising to cure it with strength

Connected to the alleged influence of international institutions was an obsession with a perceived national “weakness.” The previous regime was always depicted as weak, ineffective and paralyzed by interests other than the glory of the nation state. That weakness, it was argued, degraded the national character and led to embarrassments on the global stage. Fascist leaders promised to make their countries great again by restoring strength, order and control, curing the weaknesses of prior eras in the process.

A promise to restore law and order through violent displays of force

For fascists, force was the best solution to the threat of disorder caused by rogue and impure elements within society. To Mussolini, for example, that meant “saving” the nation from the dangers of labor unions, socialists and Marxists. To rid them from Italian society, Mussolini’s Black Shirts used violence and intimidation. He also censored the press and later outlawed opposition parties under the guise of maintaining unity.

A demand for loyalty, unity and unconditional love of country

Loyalty to the leader becomes synonymous with loyalty to the nation; one could not have one without the other. “The heart of Fascism is the love of Italy,” remarked philosopher Benedetto Croce in 1924. When an opposing party leader stood before Italian parliament and condemned fascists for voter intimidation and fraud, he was accused of being a traitor. Ten days later he was kidnapped and murdered. In Romania, where the fascist movement was closely linked with Christianity, the leader of the Iron Guard, Corneliu Codreanu, positioned himself as a religious figure whose destiny was intertwined with the destiny of the nation. Codreanu wrote in his 1933 handbook that, “all share one thought: the Fatherland, one flag, one commander, one king, one God, one will: that of serving faithfully unto death.’’

Infallibility of the party leader

Fasicst leaders were always depicted as the chief of the nation who, alone, was solely capable of leading the volk to its rightful place of destiny. In Romania, for example, Codreanu came to be viewed as a Messianic figure. In Nazi Germany, the Fuhrer was supreme. In Italy, signs at Mussolini rallies would read “Il Duce Ha sempre ragione,” or “the leader is always right.”

Imperialism

Imperialist expansion was fundamental to fascism insofar as it was necessary to further the prestige and power of the nation and satisfy its growing economic and geopolitical appetites. This was articulated by Mussolini in his 1932 Enciclopedia Italiana, in which he equated the glory of the nation with territorial expansion. “The growth of empire,” it read, “is an essential manifestation of vitality, and its opposite a sign of decadence. Peoples which are rising, or rising again after a period of decadence, are always imperialist: any renunciation is a sign of decay and death.” International institutions that limited the fascist state through treaties or “unfair” agreements contributed to its decadence.

Attacks on government employees and academic institutions

For fascists, ideas that were alien or divisive were a threat. The government bureaucracy had to be loyal to the leader and the party in order to effectuate the ideological change that society needed. As such, the previous bureaucracy was always portrayed as the enemy, responsible for the suppression of the people. Professors and scholars, too, were deemed to be among the international elites who betrayed both the national glory and loyalty to the leader. As such, they were attacked or intimidated into silence.

The recruitment of youth to carry on the cause

The Italian Fascists recruited their youth to “Believe! Obey! Fight!” It was the Italian youth that would inspire the Hitler Youth of Nazi Germany. In fascist Bulgaria, the youth were envisioned to be spiritually revived, nationally-unified and standard-bearers for future strength.

In addition to political elements, fascism also included cultural, artistic and historical elements. A shared national culture and a unified national identity were both critical to the fascist ideology, and a common tactic to achieve them was to seize control of artistic, cultural and historical institutions in order to reinforce conformity and consensus.

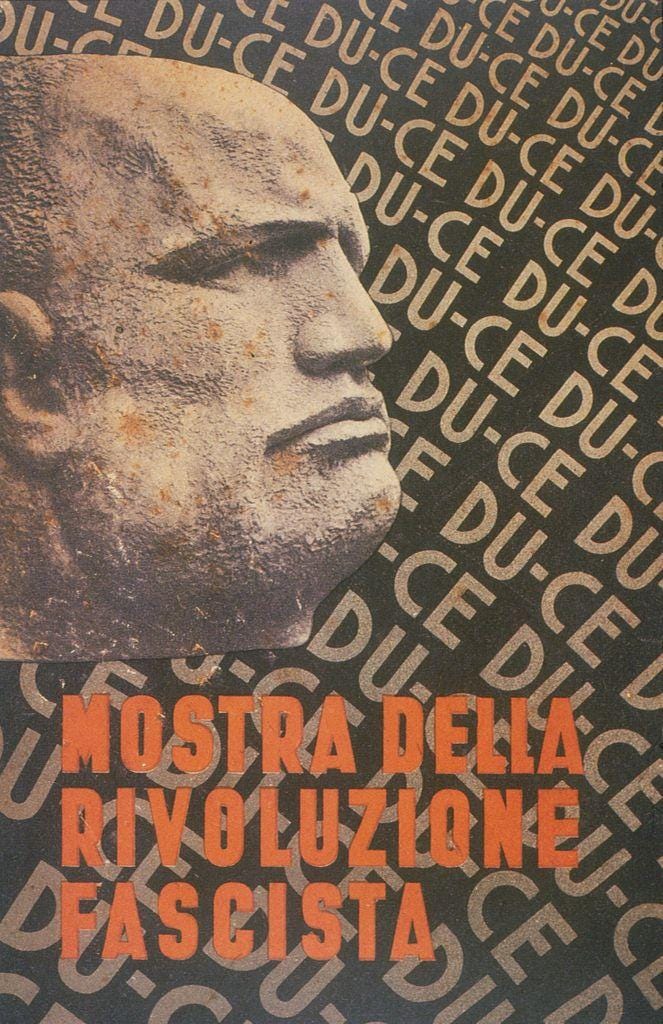

On the ten-year anniversary of the fascist takeover of Rome, for example, Mussolini mounted an art exhibit, the mostra della rivoluzionefascista (“the Exhibition of the Fascist Revolution”) replete with art, documents, and historical relics. The exhibit paid homage to the idea of a unified national culture. The fascist coup was celebrated as a pivotal moment in Italian history, with the Fascists going so far as to retroactively restart the calendar to making October 28, 1922 the first day of the year. The fascists were always the heroes; the enemies were the political Left, the socialists, communists and old-guard politicians. The exhibition was a huge success, attracting more than 2.8 million visitors; “fascism found responsive audiences, ready to have ‘Italianness’ imposed upon them,” in the words of historian Marla Stone.

The defeat of the Axis by the Allies in World War II drove European fascism into the shadows. Yet, fascism as an ideology did not disappear, and elements of it remained throughout the 20th century. In the 21st century, it has seen a revival, albeit in different forms and powered by different technologies, including social media. Why has fascist ideology proven to be so durable?

First, it should be noted that fear is a central component of fascism. Many who go along with fascist movements do so not out of genuine love for the cause but out of fear of what may happen to them if they do not conform. In the litany of fascist takeovers, the theme of appeasement recurs over and over. Fascist leaders were repeatedly appeased by those who calculated that they had too much to lose from standing up to them, or that they had enough political and social power to mitigate their effects. The leaders of the Italian government did both; they feared losing their elite status and they falsely believed their elite status would allow them to contain Mussolini. The German government of the early 1930s felt similarly; they feared Hitler but also felt that they could appease him by making him Chancellor. In both instances, they miscalculated dearly.

Still, fascism has had millions of devoted adherents throughout the decades; by 1932, there were 20 million Germans in the Nazi Party. Political psychologists have undertaken several studies to unpack the appeal, arguing that such political movements meet very real emotional and psychological needs for people. Fascist ideology promises to offer a sense of certainty, stability, identity and belongingness that individuals crave. Fascism also promises safety and security. It purports to uphold tradition, hierarchy and order. And it responds to anxieties about dangers in the world with concrete actions that reinforce predictability and control. It turns out that millions of human beings seek such order, structure and certainty in order to function—especially during periods of economic or geopolitical upheaval. Such was the case after the chaos of World War I—and in a post-pandemic, A.I.-dominated world, a similar climate exists today.

Political theorists and historians have their own explanations as to how and why fascism emerges. The British literary critic Terry Eagleton once wrote that fascism “only emerges when it has to.” “For fascism to grow rapidly,” he continued, “[economic] crisis must coincide with a defeat and demoralization of the working class.” Such was the case in Germany and Italy after World War I and in the 1920s; deep demoralization of workers coupled with unemployment, economic recession and The Great Depression. One can see a similar formula today; a demoralized working class abandoned by corporate and political elites, coupled with record-high inflation and a global pandemic.

Beyond political psychology and cultural theory, there are also more mundane appeals of fascist ideology. Fascism thrives on spectacle: large rallies, choreographed marches in matching uniforms, beautiful propaganda projected through the media. In different eras, oral histories of participants recount being captivated and mobilized by such spectacles with feelings of wonder, amazement, euphoria and pride. The genius of effective fascist propaganda lays in tying the individual participant to the broader spectacle on an emotional level; in other words, using the majesty of the large event (a rally, a parade, etc.) to manufacture a feeling of common identity and belonging. Being part of the movement to seize back a country, or to expand the power and prestige of the nation, becomes an emotional experience that even the most disenfranchised citizen can feel empowered by.

Ultimately, fascism is about power more than anything else, and that power can be both attractive and intoxicating. The French philosopher Simone Weil expressed this well in her anti-fascist writings of the 1930s. In one of her more potent works, Weil suggested that ideologies such as fascism played the role of a “phantom” in contemporary society, i.e., an illusion with no physical reality. That was because a fascist ideology was ultimately geared towards increasing the power and prestige of the nation at all costs, yet that power and prestige could never be accurately measured in the real world—and no nation ever thought it had enough of either. The need to increase national glory and prestige was a phantom cause that was continually chased but never actualized, instigating a cycle of violence and repression in service of that goal and perpetuating the very need for fascism itself. “Ideologies often promise things that they do not actually deliver,” political psychologist John T. Jost once wrote, “and this is an important part of the story of why people are attracted to them.”

The fasces in Ancient Rome were a custom of significant complexity. Evidence suggests the Romans inherited the idea from the Etruscans, and at different periods of the empire, different numbers of attendants waiting on different levels of the hierarchy would carry different amounts of fasces for different reasons.

Over the subsequent centuries, most of that complexity was lost or forgotten. During the Renaissance, the fasces became symbols of stable governments. During the American and French Revolutions, they evolved into a symbol of strength through unity; one stick alone was fragile, but bundled together the sticks became unbreakable and lethal. Fasces are still visible today across American civic spaces: at the U.S. Capitol, the Lincoln Memorial, in the Minnesota Supreme Court and even on the flag for the Borough of Brooklyn. Fasces are everywhere in the U.S., if you know where to look.

Perhaps that explains two final aspects of the fascist appeal: (1) its iconography remains littered across our civic landscape, and (2) as a symbol it has proven to be very malleable and adaptable. That is often a hallmark of an ideology that endures; it can mean one thing in one era, but shift meaning in a different era with equal potency and effect. In the present day, our world feels destabilized by technology; the unraveling of institutions; political division; and ecological collapse. A message of strength and unity, coupled with promises of greatness, reinforced with highly effective visual symbolism, can be quite appealing. As the late historian Charles F. Delzell once wrote, Italians after World War I faced the choice of “muddling through disorder and economic disarray under often inept, yet essentially benevolent democratic regimes, or falling in line behind a decisive but brutal dictatorship. Italians chose the latter. They embraced the strong man’s notions of a grand New Age. But Mussolini’s intoxicating vision of Italy as a great power, they eventually discovered, was a disastrous delusion.”

It seems that each generation must learn that lesson for itself.

Have a good week,

-JS

Thank you, Jason. Your writing and knowledge are comfortably accessible and paced.

Another aspect of why people are fearful and follow the likes of Stalin, Hitler, Mussolini, etc., according to a friend who was born in the USSR and emigrated with her mom to the US when she was 5 years old: People find freedom overwhelming and scary. Having a patriarch provide direction, resources, and few choices makes people feel secure and nurtured. --GP

An old thesis. I remember being influenced by Eric Fromm’s writings. Particularly relevant is his Escape From Freedom. Escape from Freedomhttps://g.co/kgs/FsRfFBp